A Community of Artists: Radical Pedagogy at CalArts, 1969-72

by Janet Sarbanes

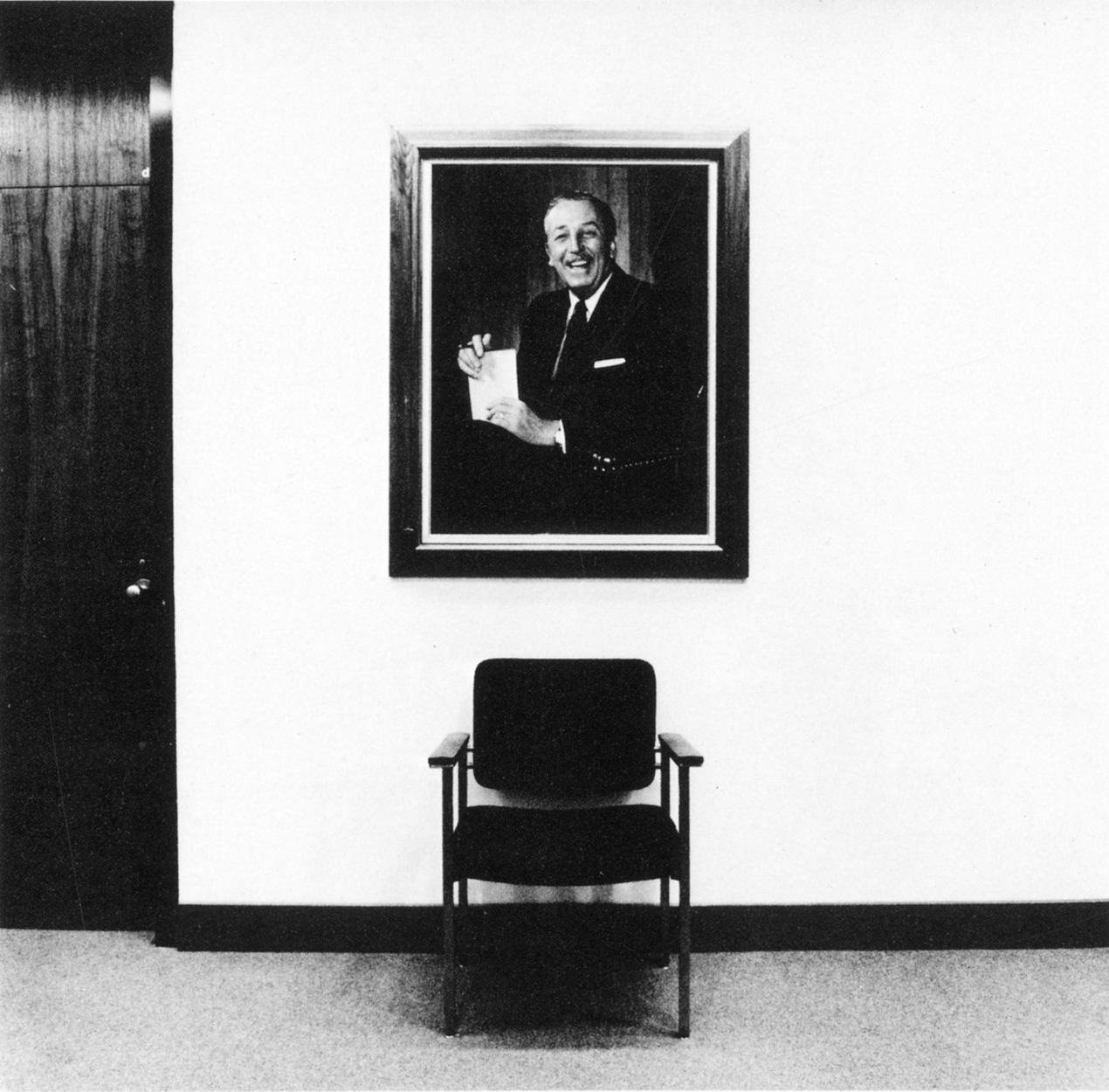

“The Founder.” Photo: Benjamin Lifson.

A painter, a composer, a drama scholar, two directors, and two radical social scientists sat down at a table in 1969 to plot the future of the California Institute of the Arts.1These were CalArts’ first administrators, and the challenge before them—and before the faculty they’d recruited for each of their departments or “schools” of art, film, theater/dance, music, design, and critical studies—was to actualize Walt Disney’s vision of bringing all of the arts together in one institution of higher learning, resulting in “a kind of cross-pollination that [would] bring out the best in its students.”2 Like the other major project occupying the last years of Disney’s life, EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), CalArts was a decidedly utopian undertaking, which its founder imagined functioning, on the one hand, like a Renaissance workshop, with masters and apprentices painting and drawing side by side, and on the other, like the nearby California Institute of Technology, where teams of scientists from different disciplines worked together to invent new technologies.

To make Disney’s dream a reality was a tall enough order, especially with Walt recently deceased (or, according to legend, cryogenically frozen), but these early organizers faced yet another, perhaps greater challenge: structuring a new school at a time of destructuration, a moment of intense political and social upheaval and radical critique of the educational system. As President Robert Corrigan observed in a 1970 memo to the Governance Committee, CalArts was taking shape at a moment when the very notion of the university or art college as a distinct institution was itself under tremendous pressure:

We [have built] educational institutions which are conceived as independent entities, completely cut off from the rest of society. […] Today our young people are determined that these walls must come down, and this is one of the reasons why our institutions are in such trouble. [Students] believe that learning must be much more than a preparation for life; it must be an ongoing process that is directly related to life.3

With the example of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement shining bright and fierce before them and with Mario Savio’s call to students to put their “bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels” of the educational system and “make it stop” no doubt ringing in their ears, the school’s organizers knew they had to formulate a radical response to this critique if the fledgling institute were to survive.4 Far from the founding of just another art school, then, the project of CalArts, in Provost Herbert Blau’s words, was “in some peculiar way to put the whole cracked world together again.”5

Deans and trustees meeting, 1969. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

In (and Out of) the Classroom

The academic program instituted in the first two years after the institute opened in 1970 responded actively to the radical critique of education, at the same time evincing a Romantic belief in the liberating and equalizing powers of art and artists. Early promotional literature explicitly redefined the notion of “school” or steered clear of the word altogether. As Judith Adler notes in her 1979 ethnography of CalArts, Artists in Offices, “reference to the new organization as an institute (with its connotations of scientific and scholarly prestige) and as a community implicitly distinguished CalArts from other schools where artists teach students.”6 The CalArts concept statement explicitly stated that “students [were] accepted as artists […] and encouraged in the independence this implies,” while elsewhere faculty and students were described as “collaborators.”7

The first admissions bulletin similarly highlighted the fact that there was to be no fixed curriculum at CalArts. Provost and dean of theater Blau advocated “no information in advance of need,” and dean of music Mel Powell called for “as many curricula as students.” The vision for critical studies outlined by dean Maurice Stein argued for doing away with courses altogether, because “courses really get nobody anywhere.” Powell’s vision for the music school was similarly anarchic and personality-driven: “We must know by now that curricula, or especially descriptions of curricula, are almost always humbug. What counts is the people involved. Expansion of musical sensibility, adroitness, knowledge, experience—that has to be operative, not catalog blather.”8

CalArts president Robert Corrigan addresses students on opening day at the Villa Cabrini campus in Burbank, 1970. Photo: Barry Hyams. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Many of the radical pedagogical impulses expressed in these early admissions materials came to pass once the institute was up and running—in its first year, on a temporary campus at the Villa Cabrini, a former Catholic girls’ school in Burbank, and in its second year, on the permanent CalArts campus in Valencia. Although the school of critical studies did end up offering courses, the options might better be described as “anti-courses”—i.e., non-academic classes parodying academic classes or academic classes in subject areas considered unworthy of study by the academy, such as Advanced Drug Research, Chinese Sutra Meditation, Sex in Human Experience and Society or Superwoman: A Feminist Workshop. Across the institute, schedules were intentionally loose and attendance voluntary.9 One of the course schedule bulletins that were mimeographed weekly and distributed on campus lists a range of classes and events, some of which repeat, others that do not: a lecture on “Epistemology of Design” is offered “at instructor’s home,” while Peter Van Riper is scheduled to lecture on “Art History or Whatever He’s Into”; a meeting with the dean of students is open to “all persons interested in discussing and working on untraditional ways of providing psychological services (Counseling, Group Therapy, Encounter Groups, etc.)”; the Ewe Ensemble (Music of Ghana) meets in parking lot W, at the same time that Kaprow offers Advanced Happenings; in the evening, a concert by Ravi Shankar.10

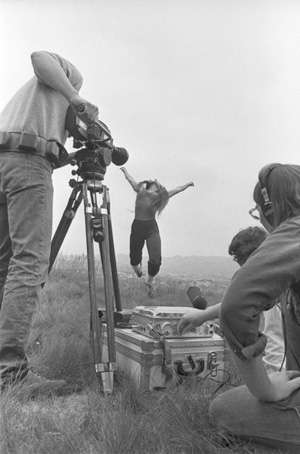

Performance at CalArts, date unknown. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Although the pressures were certainly great on Corrigan, Blau, and the deans to formulate a radical pedagogical vision for the new institute, Adler’s ethnography emphasizes the magnitude of the challenge faced by CalArts professors in actually trying to implement that vision in (or out of) the classroom. The demands of “professionalism”—long practice hours in music and dance, for instance—were frequently at odds with the demands of community, experimentation, and interdisciplinarity. The teachers who thrived in this context tended to be those who rejected the framework of professionalism altogether: “These were the musicians who did not care if their students practiced; the printmakers who were not disturbed by sloppy prints.”11

One burgeoning artistic practice of the late sixties, the Fluxus movement, was particularly suited to these conditions, and it was from the ranks of Fluxus that a number of the original faculty members were recruited, including Alison Knowles, Peter Van Riper, and proto-Fluxist Allan Kaprow in the School of Art; Dick Higgins in the School of Design; Emmett Williams in the School of Critical Studies; James Tenney in the School of Music and Nam June Paik in the School of Film. As Owen Smith observes:

The [Fluxus] worldview posits a view of the world and its operations which celebrates the absence of a higher meaning or a unified conceptual framework—seeking to open up possibilities of enactment as a manifestation of the desire to participate without fixed goals or definitive characteristics, to play, to associate, to create without a sought-after or pre-determined end.”12

Alison Knowles, House of Dust, 1967-70, installed at CalArts in Valencia, CA, 1971. Photo: Barry Hyams. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

The Fluxus artists’ interest in a more open-ended, experienced-based pedagogy and their experiments with temporality and alternative uses of space dovetailed nicely with the administration’s desire to buck the bureaucratic conventions of schooling.13 As the associate dean of the art school, Kaprow in particular had a powerful influence on the direction of the early institute. “Kaprow was the thinking behind the school as far as I’m concerned,” Knowles argues. “[He] had the vision of a school based on what artists wanted to do rather than what the school wanted them to do.”14

Another node of radical experimental pedagogy at the early institute was the Feminist Art Program, founded by Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago. Combining consciousness-raising sessions with research into women’s issues and the history of women artists, Chicago and Shapiro’s program broke with the formalist emphasis of much art and arts education of its era, encouraging students to focus on content and their personal relationship to that content—i.e., to the experience of being a woman, which had previously been discounted and/or marginalized by the universalist discourse surrounding art and art making. The program achieved notoriety through its off-campus space known as Womanhouse, a condemned mansion in Hollywood transformed by students and faculty into a giant installation commenting on women’s incarceration in the private sphere, with a progression of breast sculptures turning gradually to fried eggs on the kitchen wall, a massive collection of used tampons in the bathroom, and a mannequin trapped in the linen closet. As Arlene Raven observes, with the Womanhouse project “the nature of the work ranged from cleaning to construction, labor that crossed not only class and gender lines, but that was outside of the scope of ‘art.’”15

A third and final early pedagogical experiment of note was the Post Studio art class designed by John Baldessari, who was initially hired by the school as a painter, despite the fact that he had famously burned all of his paintings in 1970. Given the same latitude as other CalArts faculty members to decide what and how he wanted to teach, Baldessari expressed a desire to work with “students who don’t paint or do sculpture or any other activity by hand.”16 Post Studio was essentially a class in conceptual art making, for which Baldessari maintains he provided primarily equipment (Super 8 cameras, video cameras, still cameras), exposure to the exciting roster of New York and European conceptual artists he brought to campus as visitors, and exhibition catalogs. “If you had enough good artists around from all over the world,” he reasoned, “the students would come and they would teach each other.”

CalArts, ca. 1971. Photo: Barry Hyams. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Mickey Versus Marcuse

While the Dylan lyric turned cultural adage “he not busy being born is busy dying” might be considered the clarion call of CalArts in its first two years, in truth the institute was busy being born and busy dying at the same time. In a 1972 West magazine article, James Real notes that by mid-1971, before the Valencia campus even opened, “attitudes of the strait-laced Disney faction of the board of trustees toward Corrigan and Blau’s reading of the Dream were steadily stiffening with displeasure.”17 An attempt by Stein to add Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse to the faculty of the School of Critical Studies, coupled with rumors about goings-on at the interim campus that included “drugs on campus, erotic posters using D. Duck and M. Mouse characters, nude swimming in the Villa Cabrini pool” had brought home to the Disneys just how countercultural the institute was shaping up to be.18

“What really blew it,” Real maintains, “was the playful decision by a faculty member to stage a bit of radical theater by taking off his clothes during a board meeting [to discuss closing the swimming pool]. He really didn’t have to go that far to mau-mau the Disney contingent. Just putting his bare feet on the table would have done it with people who, in earlier times, had spent hours arguing over whether to put skirts around the udder of cartoon cows.”19

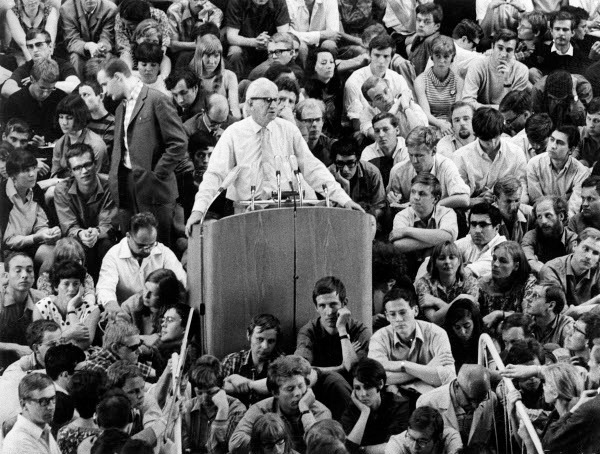

Herbert Marcuse giving a speech during a demonstration at the Free University of Berlin, 1967. Jung – ullstein bild / The Granger Collection, NYC.

Mau-mauing aside, the battle over Marcuse, a New Left hero, is significant to the history of CalArts in that it brought to the fore two conflicting notions of what this “community of the arts” might become. Stein’s vision for CalArts was deeply affected by Marcuse’s An Essay on Liberation, which put forward the idea that true freedom exists only in an “aesthetic universe.” While for the most part the “aesthetic dimension” in society functions merely to preserve the possibility of an aesthetic universe, at moments of great political change that possibility can be realized:

The aesthetic universe is the Lebenswelt on which the needs and faculties of freedom depend for their liberation. They cannot develop in an environment shaped by and for aggressive impulses, nor can they be envisaged as the mere effect of a new set of social institutions. They can emerge only in the collective practice of creating an environment: level by level, step by step.”20

For Stein and other administrators and faculty, CalArts promised to be that environment, and the form it took promised to bridge the separation between art and life, making good on Marcuse’s notion that under the right conditions, art could become a productive force in social as well as cultural transformation. In their open, improvisatory, and non-hierarchical structuring of the institute, Blau and Corrigan tried to reflect “the structure of the arts themselves,” maintaining that the time had come for “a place to exist which draws its principles of behavior from the work it is meant to develop and encourage as it goes along.”21

Blau frequently used a theatrical metaphor to describe this project: “The Institute is close to total theater […] The vision of totality being a spirit which dominates the sensibility of the arts, the task is to restore a unitary vision to the arts and to reality itself.”22The Gesamtkunstwerk was held up by Stein, Blau, Corrigan, and others as not just the model for a new form of arts education but a new form of society.23

This politically radical appropriation of the concept of interdisciplinarity or “cross-pollination” laid out in early admissions material alarmed the board of trustees for many reasons, not the least of which was its anti-capitalist underpinnings. Certainly, the trustees, many of whom were Disneys or Disney employees, would not have appreciated Marcuse’s assertion that under the new order, art would no longer serve as a “stimulus of business.”24 Indeed, the brief emergence of an aesthetic reality principle at the institute was viewed primarily as a threat to fundraising efforts, leaving the Disney family to pick up the bills. “What’s a new school, supposedly good in art, doing playing around with Marcuse?” asked board chairman Harrison Price in a 1972 interview. “Above all, a school founded by Disney people. Our credibility was destroyed.”25

Corrigan at student convocation, 1971. Photo: Barry Hyams. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Roy Disney, head of the group who controlled the CalArts board of trustees, responded to the radicalization of his brother’s concept by trying to sell off the institute to a neighboring institution. Overtures were made to CalTech, Art Center College of Design, University of Southern California, and Pepperdine University, none of which were interested (though reportedly USC might have gone for it if Disney had put up more money). In September of 1971, two months prior to the opening of the new campus, Roy decided to invest another $10 million in the school in order to create an endowment but insisted that Corrigan’s and Blau’s brief tenure at the institute had to come to an end. Corrigan had already fired Stein after the institute’s first semester, in what was widely viewed as a move to appease the board, who were still smarting over the Marcuse affair, though the president himself described the dean of critical studies’ approach as “so dadaistic that it’s causing near disaster.”26

The Trouble with Utopia Is That It Doesn’t Exist

Corrigan and Blau fought their dismissal, insisting that they couldn’t be fired by the Disney Corporation, only by the board of trustees—who to begin with refused to support the decision. Roy Disney modified his position to allow Corrigan to stay on until the end of the year, though he remained firm in his firing of Blau as provost. Blau rejected an offer to stay on as dean of theater and dance, and by the end of 1972, both Corrigan and Blau had been ousted, three years after they’d begun planning the new school and two years after it opened. The faculty was downsized, and numerous hires they had made were canceled or let go.

Notes from a faculty retreat convened in Idyllwild, California after the institute’s first year reveal that many of the original faculty and administrators themselves favored reforming the structure and curriculum of the institute, and one wonders how the school might have developed had Corrigan and Blau been allowed to stay and build on their experience. Blau, for instance, argued that “the faculty must be better structured to reflect more of a distinction between student and faculty” and “a better definition of competence, eligibility, and progress must be established” for students. He also suggested that “separate programs […] be introduced for students who are capable of directing themselves and those students who need more specific guidance.” Other faculty members cited “great dissatisfaction with the chaotic situation of the past year,” “a need for more pragmatism,” and a need to clarify “programs and degrees—their content and what they represent.”27

Paul Brach (center), dean of art, at the CalArts faculty retreat in Idyllwild, CA, 1971. Photo: Barry Hyams. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Although by that time the Disneys had donated more than $30 million to the school, much of it had gone to fund the building, which was lavishly equipped for art making, and the institute soon found itself in financial trouble. After a brief interlude with Walt Disney’s son-in-law Bill Lund at the helm, CalArts got a new president in 1975, Robert Fitzpatrick, whose charge was to assure fiscal solvency to the institute and make “all the divisions separate, to give each dean complete autonomy in his field, and to make the intermingling available to the students who could profit by it as a resource, not an obsession.”28 Fitzpatrick had little reverence for the institute’s founding vision—either Walt’s version or Blau and Corrigan’s: “The trouble with utopia is that it doesn’t exist,” he said in a 1983 interview. “And then there was this dream of the perfect place for the arts, with all the disciplines beautifully mingling, every filmmaker composing symphonies, every actor a perfect graphic artist. Sure, it’s a great idea as far as it goes. But nobody noticed that each of the arts has its own pace, its own rhythm, and its own demands.”29

What is missing from Fitzpatrick’s own vision is any reference to the more Marcusian conception of the institute not just as the “perfect place for the arts,” but as an ideal community fashioned through the arts. As Faith Wilding reflects on her experience in the Feminist Art Program and the community that developed out of it:

What remains of primary importance to me […] is the sense that we were connecting to a much larger enterprise than trying to advance our artistic careers, or to make art for art’s sake. It was precisely our commitment to the activist politics of women’s liberation, to a burgeoning theory and practice of feminism, and to a larger conversation about community, collectivity and radical history, which has given me lasting connections to people and a continuing sense of being part of a cultural and political resistance, however fragmentary the expression of this may be in my life today.30

CalArts, ca. 1971. Photo: Barry Hyams. Courtesy of California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Despite his own conflicts with the institute, Blau holds a similar perspective: “During the time I was there (I cannot speak for it now), it was—like the Bauhaus or Black Mountain—not only a school but very much what Disney wanted, a community of the arts, in which students and teachers trained together, performed together, constructed ‘environments’ together and even somehow managed—where the particular work was not of a communal nature—to leave each other alone.”31

CalArts today is a school rather than an anti-school, with grades (low pass/pass/high pass), a timetable for graduation, and for the first time in its history, a syllabus in every classroom. Yet an investment in radical pedagogy persists, with a loose consensus that the educational situations that work best often involve field trips and social outreach, project-based learning, and “mentoring” as opposed to “teaching.” The notion that faculty are to treat students as artists and colleagues prevails, with its attendant benefits and difficulties. The question of what form the delivery of content should take is a live one. Time and space are continually contested, and an openness to what might be places constant pressure on what is.

Just last year, the institute carved out a “commons” time from the heavily scheduled individual school curricula in which students can come together across disciplines to collaborate—in some sense, a return to its origins. Although, to paraphrase Marcuse, an art school can only be truly free in a free society—i.e., art becomes life only when life is also opened up to creative change—the promise of this commingling endures. Indeed, the Gesamtkunstwerk that preserves a vision of emancipated social life in times of political conservatism holds even greater possibilities in our own era of renewed resistance and collective action.