Ceremony of Us

by Robby Herbst

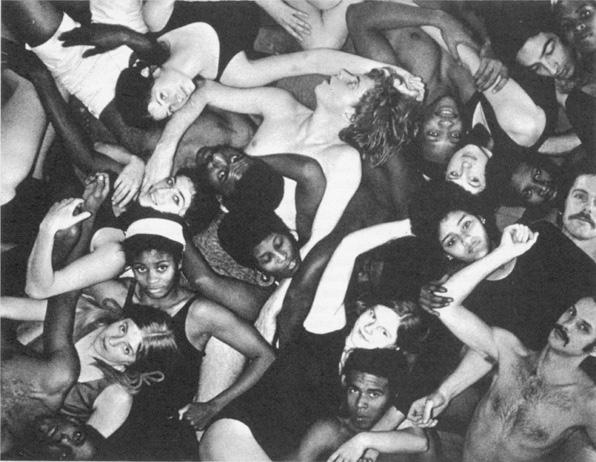

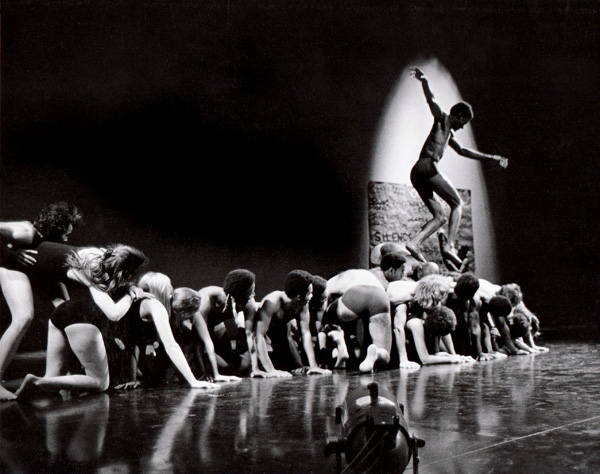

Promotional image for Ceremony of Us, 1969. Choreographed and performed by Anna Halprin, San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop and Studio Watts School for the Arts. Photo: Susan Landor Keegin.

I do my thing and you do your thing.

I am not in this world to live up to your expectations,

And you are not in this world to live up to mine.

You are you, and I am I,

And if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful.

If not, it can’t be helped.

—Fritz Perls, Gestalt prayer, 1969

After the Los Angeles Watts riot of 1965, attention and private and federal dollars flowed into South Los Angeles as a way to reckon with the shock, the guilt, and the indignation of destructive violence and rage-fueled deaths. This rioting followed a ramping up of civil rights legislation that was enacted regionally and nationally. Here in California, 1964’s Proposition 14 recertified the right of a Californian to be a bigot, nullifying the antiracist Rumford Fair Housing Act. Almost simultaneously, the national Civil Rights Act was put into law. Then, in March of 1965, the Voting Rights Act passed. It mandated federal judicial oversight of elections in states with historically racist voting practices.

In his address before a full Congress, President Lyndon Baines Johnson delivered a passionate oratory in support of the legislation. In a speech ranging from personal to universal, Johnson stated, “There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem.” Johnson continued, asserting that this “American problem,” the germ of interracial hatred, was afflicting the country’s civic well-being. Appealing to the “us” of the U.S., he declared, “Their cause must be our cause too, because it is not just Negroes but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.”1

Through a subsequent wave of utopian governmental activity, which the civic unrest and civil rights legislations spurred on, capital began to flow into the poor and minority ghettos, toward licks of empowerment. Somehow, it lit upon James M. Woods. Woods, an African American, had been a bank employee but quit that steady middle-class job improbably to become a DIY arts administrator. In 1964, just before the Watts riot, he opened an arts space called Studio Watts. He came to refer to the riot as a revolt.2

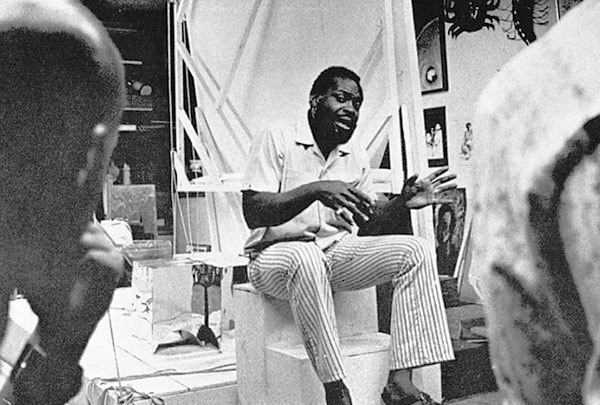

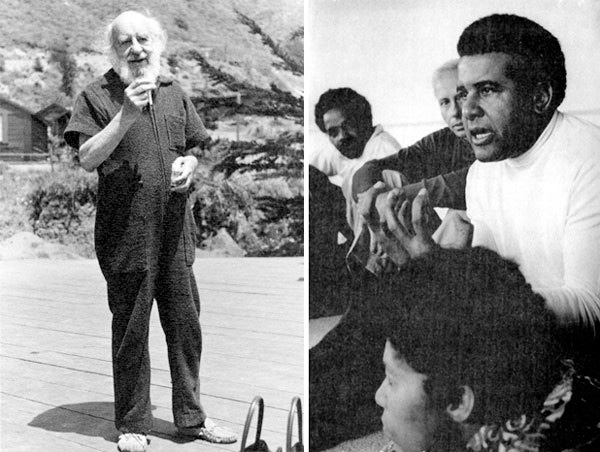

James M. Woods at Studio Watts Workshop. Photo: James Roark.

In the beginning, Studio Watts was a building on Grandee Avenue that Woods rented out to provide Guy Miller, a black sculptor, with a studio. Woods had encountered Miller’s artwork on a trip to Europe and decided he wanted to help out the local artist. In turn, Miller and a growing group of artists/masters took on the neighborhood youth as apprentices.3Woods felt that it was his calling and that in art there was the possibility of change. “Young people in the Studio have found that through art they can achieve self-awareness and environmental awareness,” the philosophy of Studio Watts, which was developed by Woods, reads. “They realize that they have a commitment and a responsibility to themselves. Because they are no longer frustrated, they are no longer alienated and can react to their environment, in whatever way they choose.”4

As the recognition of Studio Watts grew, its scope expanded exponentially.5In South LA, it became a de facto civil institution with a progressive agenda of integrating the arts into the Watts community. Studio Watts did this through an annual chalk-in, a folk art archive, design programs, media production classes and facilities, local and international advocacy, and many sorts of arts productions. In 1968, Studio Watts moved into public housing, forming the Watts Community Housing Corporation, whose goal was to develop innovative housing solutions for artists and the elderly in South LA. Somewhere along the way, perhaps when James Woods was still moonlighting as a doorman to make ends meet, the Los Angeles Music Center asked him to organize the first Los Angeles Festival of the Performing Arts. In 1969, he organized the second festival. The theme he developed for it built upon the philosophy of Studio Watts; it was “Art As the Tool for Social Change.”6

The 2nd Annual “Chalk-In,” held on 103rd Street and Grandee Avenue in Watts, 1968. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

It’s frequently commented that Watts and the rest of South LA is a world apart from the LA of mansions, beaches, movie dreams, skyscrapers, and arts venues up on Bunker Hill. This was also the case back in 1969. Then, downtown’s Music Center was a status symbol of LA culture. Its domain included the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the Ahmanson Theater, and the Mark Taper Forum; together, they provided a home for the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Los Angeles Master Chorale. It didn’t include the vanguard Hollywood jazz club Shelly’s Manne-Hole or anything down on Grandee Avenue, though Woods also programmed those off-site venues.7Onsite, the Taper was the location for the festival’s most unique offering: a movement experiment between Woods’s own Studio Watts and celebrated choreographer Anna Halprin and her San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop. The piece they created, Ceremony of Us, set itself the goal of making a dance happening of a healing encounter between conflicting races.

An Encounter

For in this performance at the Mark Taper on February 27th there will be an equal number of black and white people. What kind of partnership can evolve out of these conditions between audience–performer, performer to performer, audience members to each other. Within the defining of this question would come the answer. Not in any preconceived form but rather through a process that would permit all of us to discover in a heightened manner our own feelings.

—Anna Halprin, performance notes for Ceremony of Us8

The story goes that James Woods was at lunch, in attendance at the 1968 convening of the Associated Council of the Arts in San Francisco. There, Halprin performed a guerilla-theater-styled dance called Lunch. Woods was intrigued by the work. It used everyday movement to discursively reflect upon the conditions of eating lunch at a conference. Woods invited Halprin to participate in his upcoming festival at the Music Center.9

Having felt affected by the riot, Halprin accepted with the condition that the work be a collaboration between her dancers from San Francisco and students from Studio Watts. She would choreograph an intrinsic movement language for each group of performers, one black and the other white. The two groups would be kept separate from the other for an extended period of time. Then they would be brought together for ten days to develop a performance based upon this act of racial integration. Halprin began flying down to Los Angeles for rehearsals with the new Watts-based company in September of 1968.10

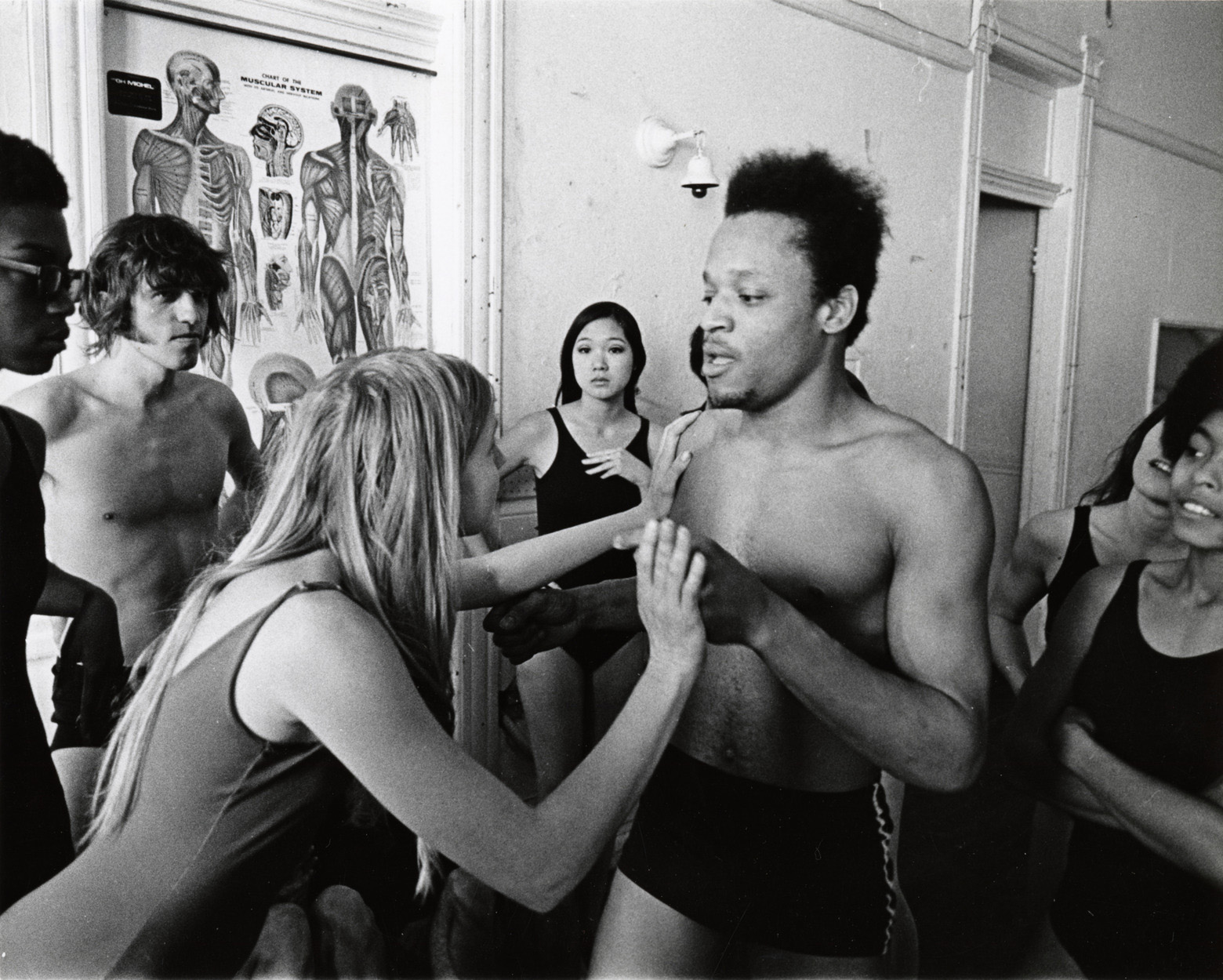

Annie Hallett and Sir Lawrence Washington, in a rehearsal for Ceremony of Us, 1969. Photo: Tylon Barea. Courtesy of the Museum of Performance + Design.

A film called Right On/Ceremony of Us captures the first days of the joint rehearsals, when the black and white troupes first met to begin developing the performance later to take place at the Mark Taper Forum.11Viewing the movie can be tedious. This isn’t to say the film lacks its charms or its psychedelic montages, but if you aren’t adept at reading racially based clichés, you’re missing much of the tension. Dialing up your inner racist and donning your stereotype goggles kicks the whole thing into gear. The abstract movements take on a storied arc, with the dancers becoming characters in an all-too-familiar movie: That’s no dancer—it’s a black primitive, a white savior, a delicate pale lily, a simple colored girl.

The experimentally styled documentary, which appears edited together from bits of group movement and verbal activities occurring in rehearsal, opens with an image of a black woman and a white woman, both in leotards, staring at each other from far corners of a wall. Cut to a shot of two dancers, black and white, making a tunnel between their hands to view the other and then a voice-over by Halprin: “We set up life situations in which two groups could break down some of those barriers and arrive at some sense of understanding and feeling of trusting each other. And the production was what happened between the two groups. It was like a collective effort, and that’s why we called it Ceremony of Us.”

Now—when the conga drums kick in to surround the essentialized dual lines of black, then white dancers—it’s as if the black dancers really are moving in a more primitive, connected, muscular fashion, while the whites affect their best Haight Street hippie dance.12Then, amidst a rhythmic movement sequence, a Watts man on his back in bridge position pumps his arms and hips up and down and up. A Frisco woman and a Watts man come together as a couple, with her writhing, splayed out on his strong shoulders. There is a quickening of the pace and tone, then some movements that can be described as scuffling and weighing out between the gendered races.

Halprin calls off the tussle with a straightforward lesson in “dropping your hips,” as she enters between the legs of a supine black man and touches his rear. The whole group together then pairs off and tries a hip-relaxation and partnered balancing exercise. They cast off in waves of mutually supported circles—where one dancer after the next leans back, neck extended, able to fully let go and yet be held up by the others—and a look of total release crosses all of their white and black, male and female faces.

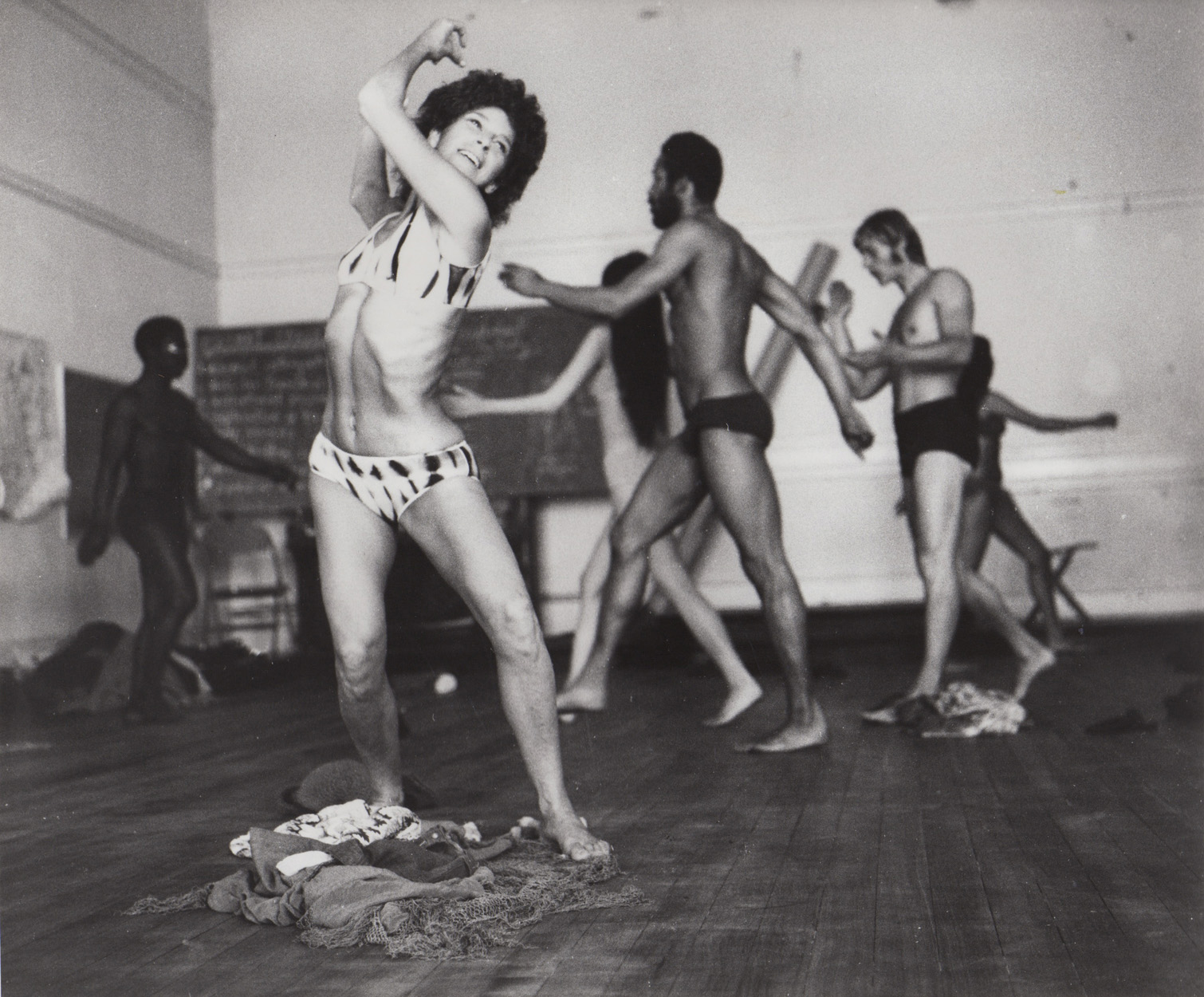

Anna Halprin with dancers from the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop and Studio Watts School for the Arts, during a rehearsal for Ceremony of Us, 1969. Photo courtesy of Anna Halprin.

There are subsequent climaxes in this short performance document, many of them involving movement and sensory games that are portrayed in the film as developing with an increased sense of intimacy, and then perhaps eroticism, between the black men and white women. I don’t doubt that insightful moments occurred off-camera, and there are insightful moments between the races recorded.13Yet the film ends with a mixed-race couple making out and the integrated crew of dancers lying together, exhausted from practice, dressed in leotards, T-shirts, sweats, and their own postworkout, postcoital, dancerly bliss.

While it may conform to then-contemporary ideas, it’s difficult not to guffaw at this radical “art as the tool for social change” happening perform a myth of the adventurous white woman and a virile black man.14Nevertheless, these same kinds of essential race and gender stereotypes—nodding toward a new age of “free”(association, love, etc.)—became part of the final dance performance at the Taper. On the night of the performance, audience members could choose to enter the theater through one entrance surrounded by a pall of black dancers or another surrounded by a throng of white dancers. How would you pick? Through which door would you pass?

Another Encounter

Attempting to move together productively within, then beyond, dividing racial tensions required the aid of a professional. The program notes for Ceremony of Us credit Paul Baum, Ph.D., as a human relations consultant for the production. Baum, who studied dance with Halprin in the 1940s before entering psychology, was invited into the workshop phase of the project and advised the dancers regarding the psychosocial conflicts that emerged.15It was also Baum who introduced Halprin to psychotherapist Fritz Perls in 1964.16

At Big Sur’s Esalen Institute, Perls developed Gestalt therapy, a dynamic tool to work through the personal and socially constructed blocks that limit an individual’s potential.17Interested in improvisational movement in her dances, Halprin found the mind-body connection to be a profound inhibitor of creativity. In her extensive biography Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance, performance historian Janice Ross explains, “Ann was discovering that the more she used structured improvisation to free herself and her students from habits of moving, the more her students would occasionally, and unpredictably, erupt emotionally, crying and becoming distraught in a way that perplexed her and left her feeling helpless.”18In sessions with Perls, Halprin and her dancers discovered that they were able to recognize these somatic limitations and move beyond them, move in a freer, less hung-up manner.

Left: Fritz Perls at Esalen, 1967. Photo: Gene Portugal. Courtesy of Pam Walatka. Right: Price Cobbs (right) with George Leonard (center) leading a racial encounter group, 1970. © Paul Fusco/Magnum Photos.

At Esalen, a series of therapeutic racial-confrontation workshops was organized in 1968 by George Leonard, a white journalist (and later president emeritus of Esalen) who wished to expand upon the personal liberations he’d witnessed there, applying Gestalt techniques to work through the “blocked dynamics” existing between races. He convinced a reluctant black psychiatrist, Dr. Price Cobbs, to join him in the endeavor.19The registration form for the workshops read:

“Open racial confrontation is at last a reality, but it has brought bloodshed and death, terror and polarization. Rather than fear a confrontation, we must welcome and embrace it. For only in direct and honest encounter can white racism and black self-hatred be discarded. This series of Racial Confrontations is to allow for bloodless riots where the most dreaded thoughts and emotions may be expressed, where self-delusions that limit can be stripped away. Only when such confrontation has occurred can man expand his blackness and whiteness into creative humanness.”20

The story of this experiment with staged racial encounter is told in part through Adam Curtis’s four-part essay film, The Century of the Self (2002).21In the film, Esalen’s experiments with group psychology are discussed as an instrument for social change, using archival footage of what we assume to be that workshop. A circle of chairs occupied by blacks and whites surround a central speaker. The edited footage shows blacks as they tear into the white “radicals” and “liberals” who had signed up for the racial abuse Curtis choose to highlight:

I’m looking at you, whitey. You got clothes on. You got shoes on. You got the goddamn police in the neighborhood. You got a government. You got a mayor. You got the president. You got ambassadors. You got the deaths in Vietnam. That’s the benefits of slave labor. You got buildings, skyscrapers, that you dominate and control, economically and politically, and tell me that it is not yours. Don’t give me no shit about how I am free. You’re a goddamn liar, you white-pink son of a bitch, you.

Leonard, in an interview, discusses the methods and outcome of these encounters:

We thought that we wanted to get that kind of black-white confrontation so you could really get down to see what was between the two races. Not by backing off and trying to be polite, but by going right into the belly of the beast, of this beast of racial prejudice. And these were extremely dramatic. These were the toughest workshops ever convened at Esalen Institute.

In his documentary, Curtis says that the workshops were deemed failures. Plausibly, but also clearly working on a theme he was developing in his essay film, he states that black radicals rejected these sorts of encounters, that Esalen’s Gestalt-influenced project of confronting individual blocks (i.e., mutually racist attitudes) toward the goal of a deracinated subjectivity was inherently destructive to the source of black power itself—a collective black identity.

Jessica Lynn Grogan tells it slightly differently in her book, A Cultural History of the Humanistic Psychology Movement in America. According to Grogan, Esalen’s first race workshop was indeed difficult, but she points out the class dimension of the whole undertaking. All of the participants, black and white, were middle class with the exception of one “anomalous” black road worker who stumbled into the group, almost by chance. Grogan says that from the beginning, much of the tension in the racial-encounter session developed between the black participants themselves. The session’s lone black woman lit into the black men. Grogan confirms that the session then evolved into a full-on black-on-white racial spew but says that this initial event was, in the end, deemed a success by Leonard and Cobbs and not the immediate failure that Curtis suggests. As the workshop was nearing its end, a white woman cried out that she only dated black men because she’s found white men to be so disappointing, and a kind of cathartic and empathic bond set over the group.

Grogan’s wider thesis for her chapter on Esalen and humanist psychology is that liberals, lacking a serious connection to racism, were never able to fully commit to the radical potential to racial encounter within psychology. Esalen continued to have racial-confrontation workshops through the early 1970s. It even opened a San Francisco center so that it could involve itself with the needs of the urban populations, but the urban campus suffered from a lack of funds from its mother organization in Big Sur and eventually closed.22

Ceremonies of Us

Martin Bernheimer’s Los Angeles Times review of the February 27, 1969, performance of Ceremony of Us at the Taper begins by painting the scene of the 400-person courtyard frolic that developed at its very end:

A few girls were swinging happily from tree branches, a mini-mob was executing a convoluted snake-dance, some hardy souls were bobbing up and down piggy-back, a few terpsichorean pros were waving monstrous plastic streamers over the participant’s heads, and a pair of ambulatory percussionists kept everything moving with the beat-beat-beat of their tom-toms.23

As for the dance performance itself, Bernheimer was mildly amused by the “handsome young people who obviously enjoy freedom from inhibition” but found the “deep mystical significance, which is supposed to pervade a Halprin performance, elusive.” Demonstrating familiarity with Halprin’s career, Berheimer traces a trajectory from her “Humphrey-Weidman-Margaret H’Doubler training” to now concerning herself, instead, “with the expression and solution of philosophic problems in symbolic, physical terms.” And that’s where the rub lies for him. Though he doesn’t come out and say it, others do: Is this sort of interracial encounter meant to be a stage show?

Ceremony of Us, 1969. Choreographed and performed by Anna Halprin, San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop and Studio Watts School for the Arts. Performance at the Mark Taper Forum, February 27, 1969. Photo courtesy of Anna Halprin.

Ross sees Ceremony of Us as a transitional piece for Halprin, a moment when stage works began to have less relevance for her and the act of making dance with specific communities as a shared experience mattered more. Her book documents an extensive backstory to the work, including notes from the dancers of both Watts and San Francisco about their involvement in the preliminary workshops, the joint workshops, the performance, and the series of critical dialogues that followed it. She writes:

In Ann’s attempts to converge the ideological and the aesthetic, the aesthetic lost out in Ceremony of Us. Success in the world of the studio’s reality—a frank performance of tasks, for example—doesn’t automatically equate with success on the public stage. In addition, Ann’s efforts at making social morality the score for the piece had confused theatrical performance and ritual. Even though Ann was creating a theatrical work out of real emotions and encounters of her two groups of dancers in Ceremony of Us, the performers’ attempt to substitute a theatrical presence for a real life one were necessarily incomplete and ambivalent.24

Many African Americans from South LA are said to have made it to the performance at the Music Center. Bernheimer doesn’t specify whether they were among the revelers outside the theater afterward, but I desire to presume that this population integrated joyfully in the Ceremony’s courtyard be-in. The day after the performance, Woods hosted a public evaluation and review of the festival activities at Studio Watts as a part of the festival itself. In her book, Ross chronicles this get-together as a rough comedown from the buoyant, carefree, treetop frolic at the Taper that Bernheimer describes.

In later years, Halprin’s choreography would partly develop along the lines of what came to be known as community art and perhaps today as social practice.25It’s not difficult to imagine reworking the precepts of Ceremony of Us or Esalen’s racial-encounter workshops into contemporary social practice artworks in the tradition of antagonism or public pedagogy, as described by art theorists Claire Bishop and Grant Kester, respectively.26In this contemporary reimagining exercise, the context is not the Watts riot, nor the 1960s civil rights struggles. It is not the wholly essentialized identities explored in the historic works. It is the divergent perspectives that have come to define our differing, and at times nuanced, perspectives of the Trayvon Martin murder and the 2013 amendments to the Voting Rights Act. It is also our nation’s divergent perspectives upon the significance of “us” constituting the United States Of America.27