John Baldessari: Cut to the Chase

by Leslie Dick

John Baldessari’s work is primarily regarded as an extended humorous meditation on the nature of art itself; he is notorious for cremating his own paintings, commissioning others to make his artwork, and admonishing himself to make no more boring art. The major survey exhibition, “John Baldessari: Pure Beauty,” jointly organized by the Tate Modern and LACMA, opens up multiple alternative approaches to his work. Baldessari is an extraordinarily productive artist, and he continues to make new work, often referring to earlier interests and obsessions. Over the years, his work has consistently been seen as more playful than analytic; yet if we cut another tangent across the field of his production, coming at it from the 1980s or later, rather than the 1960s, a very different set of strategies and ideas is revealed.

John Baldessari, Fissures (Orange) and Ribbons (Orange, Blue): With Multiple Figures (Red, Green, Yellow), Plus Single Figure (Yellow) in Harness (Violet) and Balloons (Violet, Red, Yellow, Grey), 2004. Acrylic, 3-D digital archival print with acrylic paint on Sintra, Dibond, and Gatorfoam panels. 10 x 18.75 ft. x 3.5 in. Courtesy of the artist.

The large diptych Fissures and Ribbons (2004) [full title in above caption] shows the figure of a helpless man tied to a suspended chair. Using two found photographs, one color, one black-and-white, and eradicating the faces in both photos with his trademark dots and color silhouette techniques, Baldessari presents two protagonists, one implicitly heroic, the other not so much. Wearing a military uniform, arms crossed, sitting upright, the hero figure is carried on the shoulders of a crowd of celebratory men, draped in streamers and balloons. The scale of the image, together with the grandeur of his pose, invoke history painting, as well as movies about World War II. The second protagonist, equally faceless, is tied into a wooden, wheeled desk chair, hanging from an invisible support, as two men wearing ties jump or fall into empty space behind him, and the building around them collapses for no discernible reason. This section is marked with orange painted lines, echoing the orange and blue painted streamers that festoon the hero’s celebration, yet here the painted lines represent lines of fracture—fissures—which show how this world is coming apart, as if under the strain of its own contradictions.

Falling, hanging, raised up on the shoulders of others: these variations on a theme invoke a set of ideas around masculinity that emphasize dependence and passivity as the obscured verso to man’s perpetual obligation to be autonomous, a perpetrator rather than a victim, active rather than passive. Paradoxically, the hero’s power, his success, is manifest in his being carried by others, precisely in not standing up for himself, not standing with his feet firmly on the ground. The tragic clown or puppet in the hanging, swinging chair on the left is perhaps being rescued, perhaps tortured, perhaps merely tossed in the air. In Fissures and Ribbons, being off the ground, falling, jumping, raised up by others becomes imbued with uncertainty, insecurity, until suspension itself becomes equivalent to that unthinkable threat, dependency.

Paradoxical also is the Baroque quality of this work: the proliferation of streamers slice through the image, cutting it to pieces and tying up the hero in a tangle of ribbons. Is he a gift, wrapped? Is he somehow feminized, subordinated to the decorative furbelows that fall around and over his body? Or is he caught in a net, just as “tied up” as his double, the man hanging in his chair/harness on the other side? Activating a surface through dynamically opposed colors (orange and blue), these sharp ribbons are key to the representation of power and powerlessness.

The Baroque is all about intensity—of emotion, of ideas—and that intensity is conveyed through and materialized in movement, in dynamic action. Visual elements belonging to the Baroque include mobile lines; intense and reflective colors in the garments worn by angels and other celestial beings; the flow and break of architectural forms, concave, convex; and, last but not least, the trickster quality of trompe l’oeil. Baldessari is a different kind of trickster—more of a joker, maybe. But the feverish movement that belongs to Borromini’s Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza (1640–50), to Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1652), to Pozzo’s insanely deceptive ceilings in the church of San Ignazio (1685–94), to the flying and/or falling of Tiepolo’s paintings, such as Nobility and Virtue Triumphing over Perfidy (1744)—this spirit is echoed in Baldessari’s Fissures and Ribbons, despite and because of its explicit postmodernity.1

Baldessari’s integration of elements drawn from painting, photography, design, and architecture (in the large mural work) is clearly a crucial dimension of his project, which repeatedly invokes these other histories, in particular the history of art. Ultimately, however, his work is rooted in a prolonged consideration of photography and inevitably involves thinking about cuts, as each photo’s framing slices it out of its surrounding reality. During the 1980s, his fascination with the power of the cut became central, as photographs were cut up and into compulsively. These cuts included reframing the photograph, decapitating the figures in the photo, reducing the figures to silhouettes, flat outlines, or areas of color, and recontextualizing each image in relation to other images, slicing at its specificity until narrative fell away. His work demonstrates the ways in which the ideas derived from this exploration of photography—that meaning is generated through breaks and sutures, cuts and contiguities—extend to include all images, and indeed, thought itself.

By reframing and juxtaposing images, Baldessari’s work proposes the photograph’s original frame as a cut, insisting that, whatever the context, each photograph operates in juxtaposition to the objects and the space around it, like a collage, a visual collision. That quintessentially 20th century form, collage, and its familiar, montage, are all about the cut. The paradox that John Baldessari’s later work explores is that the cut and the seam are one and the same. Without the cut, which decontextualizes the image, the juxtaposition with another, disparate image cannot take place. In other words, Baldessari’s work deals with photographs in such a way that it is impossible to avoid thinking about the deep structures of photography itself.

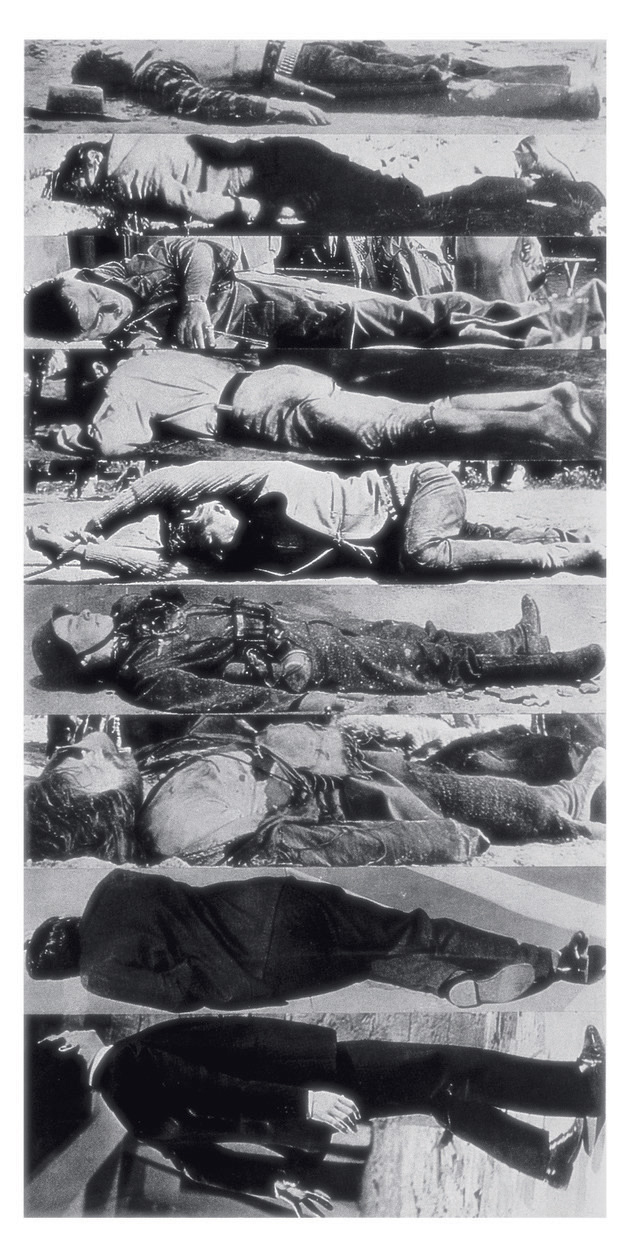

John Baldessari, Horizontal Men, 1984. Gelatin silver prints, 8 x 4 ft. Courtesy of the artist.

There is a violence implicit in these cuts. The lines of fracture that mark the site of each cut are clear, as if to emphasize the sharpness of the implied knife. Digital technology does away with the actual cutting implement, needless to say; nevertheless Baldessari’s project activates a sense of slicing and splicing that points to the buried violence of the cinematic form. Cinema constructs a fictional reality by cutting up and suturing together bits and pieces of moving images. The editing that makes up movies (and TV) constructs a sense of lived reality, as we edit our own memories and experiences into narratives that echo the structures provided by these forms. We come to know ourselves, and to recognize our lived experience, through the edited and reconstituted stories that surround us, in advertising, TV, movies, and all the other moving images that break up the space of every day. Yet there can be no suture, no healing reparation, without the violence of that initial cut into space and time.

Baldessari’s work of the 1980s exploits his huge collection of film stills, and it is significant that the film still is not a “frame capture”—it is not a quotation or excerpt from the sequence of images that run, frame by frame, through the projector.2Parasitic on the main production of the movie, Hollywood film stills are displaced: produced by a photographer who makes a set of still photos that bear a relation to the narrative situations of the film, yet are not subsumed by it. Hollywood film stills are not portraits of the actors, nor do they function as documentation of the shoot. They tend to depict a dramatic situation that has its own internal dynamic, without the support structure of the surrounding narrative. In other words, film stills imply a set of relationships or actions, but without the context that fills in the realistic continuity and allows the viewer to participate through identification and narrative satisfaction. Disrupting that system of satisfaction is part of Baldessari’s project, and the film stills themselves might be seen as momentary interruptions in what is otherwise presented as an easily decipherable, almost inevitable flow.

Film stills are useful to Baldessari precisely because they are detached from the movie, cut away from their meaningful context. His inventory of film stills constitutes a deep image bank of 20th century American culture, a proliferation of images that haunt us, or at least those of us old enough to remember watching black-and-white movies on TV in the afternoons after school. Arguably those born after about 1980 have internalized an entirely different kind of image bank, a digital one, which exists without limits, instantly available, taking up no space, and requiring only a wireless connection and a screen.3In any case, Baldessari’s image repertoire invokes a circulation of unspecified yet familiar narrative situations, which move through our unconscious, constituting material forms on which we can project our individual lives. The prevalence of black-and-white film stills in his work only adds to the sense of haunting: after all, ghosts exist on a grey scale, they repeat themselves, and they can’t leave.

I use the word haunting intentionally; the vast majority of Baldessari’s film stills are from movies we’ve never seen, or can’t remember, movies we don’t recognize: B movies.4Yet we recognize them as movies, and we may hypothesize about the dramatic situations merely from the relationships between the figures and the objects in the image. Or not: Baldessari drains the photo of its dynamism, its energy, and then it is reactivated, gaining momentum through the implied violence of the cuts and splices which make up Baldessari’s work. The types that appear and reappear in these images may serve as proxies or stand-ins, representing the repetitive routines that drive our unconscious life, destined as we seem to be to repeat ourselves, no matter what. Like the figures frozen into dramatic tableaux in these film stills, ghosts find it hard to move beyond their destiny; like us, they are stuck.

Baldessari repeatedly uses a colored circle to cover the faces of the photo’s protagonists. The circles are very flat against the black-and-white photographs, superimposing an abstract pattern—or perhaps some kind of aesthetic or sociological analysis—on the image. Their bright colors emphasize the playfulness of this action, and its effects. The dots are usually all the same size, although the faces they obscure may be different sizes. It’s as if another system (the dot pattern) is overlaid on top of the image, inviting us to connect the dots, or draw a diagram of some kind. Yet the disc or dot functions primarily as a mask, reducing the characters to types rather than individuals. The eradication of the faces with these discs impels us to read past the clichéd situation, searching the image for clues, to look more closely at the relationships, the bodies, the positions, to see what there is to be seen.

Baldessari has said that his first use of the dot was a blank price sticker, available at any stationery store, which he used to de-face certain media images of bourgeois life that disturbed and infuriated him.5When the circles are white, they bring to mind a hole-punch, which seems more aggressive than merely superimposing the circular disc, or possibly a very neat, stylized bullet hole, more aggressive still. Something is missing, something has been subtracted, and as viewers our impulse is to compensate, to fill in the blanks. Evidence of violent interventions into the image elicits a response that tries to repair the tears, to sew it together again.

Much of Baldessari’s work from the 1980s participates in a dialogue with a number of his contemporaries who were exploring questions of sexual identity and representation through photography and text.6Baldessari’s interest in making the gaze explicit, in a number of works from this period, such as Man and Woman with Bridge (1984) and Spaces Between (Close to Remote) (1986), belongs to this historical moment.7During this period, Baldessari also produced a series of works that explicitly deal with issues of masculinity and representation. Arguably, he shifts away from the category of Conceptual art to take up some of the political and aesthetic concerns of a younger generation, bringing his own wit and insight to the party, and extending the conversation started within feminism, to venture into the minefield around the topic of masculinity.

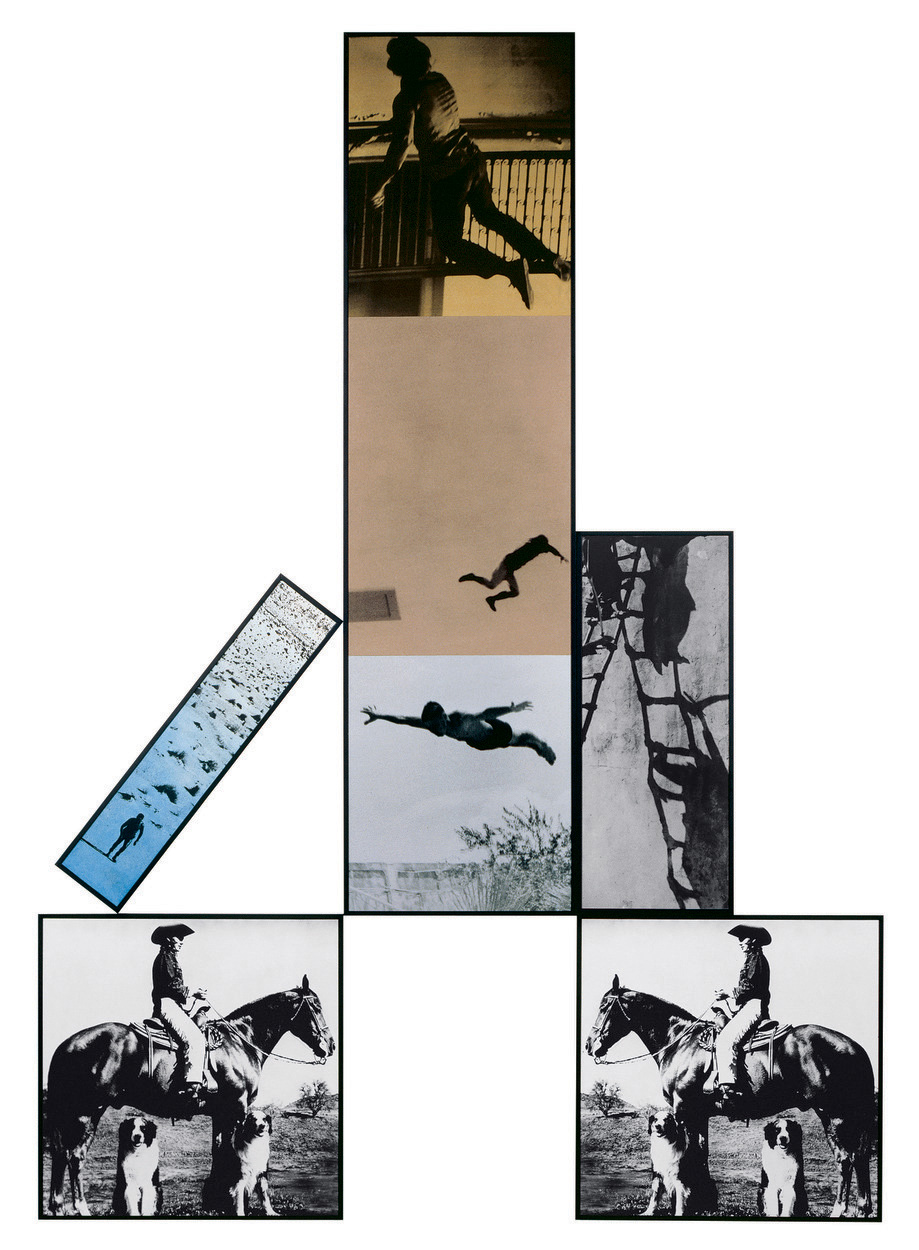

John Baldessari, Upward Fall, 1986. Black-and-white photographs, oil tint, metallic paper, 8 x 5.75 ft. Courtesy of the artist.

In Horizontal Men (1984) Baldessari stacks a number of narrow rectangular black-and-white photographs of prone male bodies, one on top of the other, to make a tower. At the very bottom or foundation of this heap, the man in a suit is not lying down, but somehow both standing and falling. Baldessari’s intervention, cutting him out of his context and rotating the image until he is horizontal, underlines the figure’s powerlessness. The next photo in the stack shows a figure who could be the same man-in-a-suit, now completely unconscious. Out of this before-and-after sequence, the other men appear, seven different iterations of the same theme. These men are damaged, wounded, or dead. The images provide a residue of violence, some fictional, others apparently real. There is an eroticism to these men’s bodies, their very passivity evoking an aggressive sexuality; the cowboy constrained by rope is particularly seductive. As the eye travels over this set of images, the buried joke (that all these prone men add up to a phallic tower) emerges. Baldessari has once again found a way to represent the fundamental semiotic structure, showing how signs hold meaning only in contrast to other signs, and only within a system of dynamic oppositions. In other words, men’s power rests on and against ideas of powerlessness, and without the shadow of a pathetic, wounded masculinity, triumphant man cannot possibly exist.

Some of these works recall the structure of altarpieces, as if to underline the phallic aspect of their symmetry and verticality. The shape of Upward Fall (1986) is explicitly phallic, while inverting an image of a falling man above two pictures of male figures jumping and diving. A shadow ladder supports one side, a solitary man lost in the desert is propped insecurely on the other. A visual meditation on rising and falling, it brings to mind Freud’s wonderful note on flying dreams as erotic: “For the remarkable phenomenon of erection, around which the human imagination has constantly played, cannot fail to be impressive, involving as it does an apparent suspension of the laws of gravity.”8

Upward Fall also invokes a Goya painting, El Pelele (The Puppet) (1791), which shows a group of young women tossing a life-size dummy, dressed as a man, in a sheet.9In Goya’s painting, the loose figure of the thrown body, at the mercy of the smiling women, becomes an emblem of male passivity. In this context, the differential between a male body upright and a male body falling, suspended, or prone, becomes the dynamic opposition where masculinity is defined, hovering in the indeterminate space where the words pendant and dependent overlap.

Another symmetrical structure, disrupted, occurs in Planets (Chairs, Observer, White Paper) (1987). Making a visual pun on his own use of dots, Baldessari adds (or subtracts) blank circles to a found photo of planets, as if to ask, what’s missing? This loaded question seems pertinent in relation to the question of masculinity, as once again Baldessari places reflecting images on either side, as supports to the main picture. Yet the figures in these two photos seem to hang off the larger one, suspended in some way. The two side photos show men immobilized in chairs, apparently upright, but bound and gagged, on the left, and on the right, in a wheelchair. As time passes, it becomes clear that again the image of the gagged man tied to the chair has been rotated. What was read initially as a wall (from which the chair seemed to be hanging) is in fact the floor: he is tied to a chair and lying on his back on the floor. The wallpapered wall and patterned carpet make the image indecipherable, like a dream memory of being tied to a chair and somehow hanging. On the right, the old man appears to be falling out of his wheelchair, again a patterned carpet and floorboards rise up to meet him in a distortion of space that disorients the eye. Like the hanging man in Fissures and Ribbons, from 2004, both these men are powerless, both of them apparent victims of some kind of violence. Above it all, a set of serious men exchange looks, as if frozen in asking the question: what happened here?

The profound connection of violence and the representation of masculinity is outlined in these images where violence is implicit, measured through its effects, in the passive male bodies that are its residue. The suspension of gravity itself becomes the unconscious metaphor that stands in for what Baldessari has called “priapic” masculinity, while the silent planets appear to float, weightless, both trapped and supported within a gravitational force field.10

In Baldessari’s legendary archive of movie stills, it is said that the largest categories were the kiss and the gun.11 How does Hollywood (and our imaginary) represent the action hero? With a gun and a car, of course. Or a horse. Or maybe a rocket. Kiss/Panic (1984) uses ten black-and-white shots of male hands holding guns as a decorative frame radiating outward (like Bernini’s frieze of golden rays that frame Saint Theresa’s shuddering body). At the center Baldessari places two photographs: a close-up of a kiss, in which the faces are almost melting into each other, and what appears to be a documentary photo of the aftermath of some kind of public event, showing people running in all directions, chaotic, intense, and once again, indecipherable. It could be an outdoor concert, a scene of violence, or merely an image of multiple urgent movements, allowing an intensity of feeling to coalesce.

John Baldessari, Buildings=Guns=People: Desire, Knowledge, and Hope (with Smog), 1985/1989. Black-and-white photographs, color photographs, vinyl paint, oil tint, 15.5 x 37 ft. Courtesy of the artist.

Buildings = Guns = People: Desire, Knowledge, and Hope (with Smog) (1985/89) displays a fascination with the photograph as monumental façade, an uncompromisingly perpendicular presentation of a thing or event. Measuring 11 by 26 feet, even larger than Fissures and Ribbons, its impact is like a billboard up close, both blank and overwhelming. There is no life, no movement, in the black-and-white photos of banal civic occasions, stilled for the camera, or the mere flat facts of the gigantic guns, the gridlike modern office block, or the kiss. Each of these is virtually interchangeable, as the title insists, and the sentimentality implicit in a blue rose or a bitten apple cannot mitigate against the full-on flatness of the wall-size image. The dots that obscure the ordinary faces in the photos are all white, like bullet holes. It’s grim, it’s beautiful, it’s funny–it’s a map of American life.

In recent years, the gun has disappeared, leaving the nose and ear, elbow and knee, as comic stand-ins for masculine/feminine, concave/convex, active/passive. Questions of gender and representation still circulate through Baldessari’s work, in a dance of metaphor that no longer foregrounds the violence of cutting, so much as it celebrates the playfulness of putting elements together into new configurations.