Kalifornienträumen: Bertolt Brecht’s Los Angeles Poems and Other Sunstruck Germanic Specters

by Quinn Latimer

On thinking about Hell, I gather

My brother Shelley found it to be a place

Much like the city of London. I

Who live in Los Angeles and not in London

Find, on thinking about Hell, that it must be

Still more like Los Angeles.

—from “On Thinking about Hell,” Bertolt Brecht

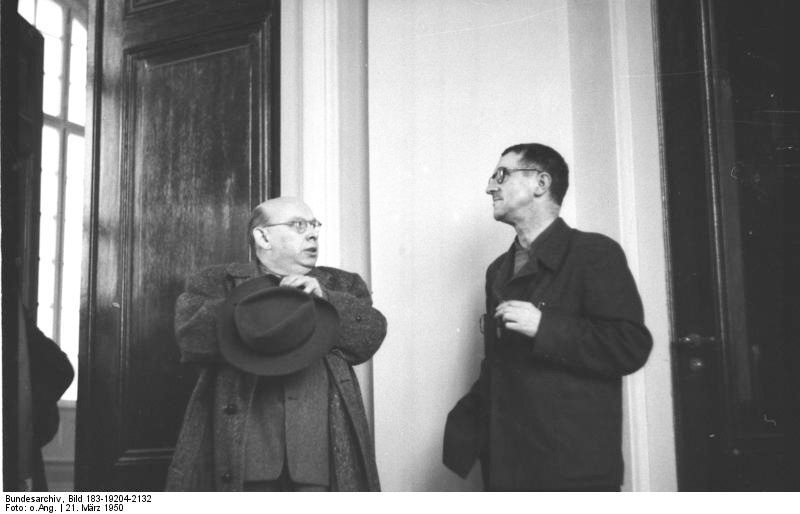

Bertolt Brecht and Hanns Eisler, 1950. Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst – Zentralbild (Bild 183). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Los Angeles has long been an urban dialectic par excellence, with its discordant melodies and apparent contradictions; its extreme polarities of nature, of culture, of economics, of politics. The metaphors come easily—the tropical flower abloom in a desert basin, the city of illusions, etc.—and Bertolt Brecht employed them acidly and exactingly in the poems he wrote during his LA exile in the 1940s. Indeed, at no time, perhaps, was the city’s surreal admixture of improbable light and equally improbable darkness (sunshine and noir, in other words) more startling than during that very time, the thirties and forties, when hundreds, perhaps thousands of Weimar-era German-speaking exiles (Brecht, Theodor Adorno, Alfred Döblin, Fritz Lang, Peter Lorre, brothers Thomas and Heinrich Mann, Arnold Schoenberg and Salka Viertel, among them) fled the killing fields of World War II Europe and found themselves in a city of angels nestled along the cerulean pool of the Pacific.1

It is hard to imagine them there. Brecht on the beach, Döblin taking the bus along Crenshaw Boulevard, Thomas Mann writing Doctor Faustus under the palms of the Palisades. And although most of the exiles returned to Europe after the war—many of them, including Brecht, hounded out by the reactionary fervor of the House Committee on Un-American Activities—the traces they left on Los Angeles, and on American culture through the ever-disseminating film industry, are indelible. For example: the idea of the modern dialectic? Adorno, whose Frankfurt School relocated to LA for the duration of the war, and who there wrote the seminal 1947 text Dialectic of Enlightenment with fellow exile Max Horkheimer. Film noir? Brecht’s good friend Lang, whose 1931 Berlin film M arguably inaugurated the genre that found its fullest form in forties-era Hollywood, in a film industry immeasurably advanced by the hundreds of World War II exiles who filled it. And the poetry I used to begin this essay, for its brilliant and cogent and ironic invocation of the city, is by Brecht himself, of course. No less than Adorno’s critical theory and Lang’s film noir, the caustic clarity of Brecht’s Hollywood-Elegien left their mark on the city that inspired them, as did the exacting Marxist Berliner who authored them during his bewildering exile in the breezy climes of Santa Monica.2

Hell to him and home to me, though that can also be close to the same thing, no? But more on that later. Because in spite of the great and lasting work done in LA by Brecht, I only became aware of it and him when I got older. As a child growing up along the California coast in the 1980s and ’90s, first in Venice and then an hour north in Ventura, I made my first acquaintance with the lingering specter of this Germanic, Middle-European presence in the built landscape that surrounded me. Southern California, oh land of light and horizontals, has an architecture to match: California modern. Its famous instigators, the Austrian Jewish architects Richard Neutra and Rudolph M. Schindler, were not quite exiles but rather émigrés who had come to LA a decade earlier, in the 1920s under the heady influence of Frank Lloyd Wright. Though their most famous buildings are modernist homes nestled in the hills, and the ever-influential Schindler House in West Hollywood, I first came under their influence when I began kindergarten (shades of Germany there) at Westside Alternative School in Marina del Rey.3

Westside and all the subsequent public schools I attended, which share a specificity of architecture that feels ingrained within me—the L-shaped, one-story classrooms clad in peach-colored stucco and connected to each other by long, covered outdoor concrete hallways, often alive with the shriek of skateboards, for which they seemed to be made expressly—were direct descendants of Neutra’s 1934 “test-tube school” in Southeast Los Angeles.4(In this sense, Neutra may be said to be one of the grandfathers of skateboarding, having created the very architectonics of the sport, those schools of long, fluid surfaces that were no less integral than the empty concrete pools of drought-ridden seventies-era LA; but I digress.) Until Neutra designed the Corona Avenue School in Bell, California, public schools aped the architecture of their Eastern sisters: big, stolid brick buildings that would not have been out of place in Berlin or Vienna or any packed urban metropolis.

Neutra’s design, like his California modernism in general, took the sprawling and sun-bleached LA landscape into account, making a school that was long and low and minimal and various, letting the elements—light and air—shape it as much as his materials. Neutra’s and Schindler’s architectural philosophy was very much a welcome acknowledgment of the natural world of the West Coast coupled with geometric modernist aesthetics. The Schindler House, for example, was a modernist approximation of a camping lean-to. Or as Schindler himself wrote in 1952, “In 1921, with the impact of California fresh on my mind, I built my own house, trying to meet the character of the locale. […] I introduced features which seemed to be necessary for life in California.”5

Rudolph M. Schindler’s house on Kings Road, West Hollywood. Photo: Grant Mudford. Copyright the artist.

It’s interesting to note then that, in contrast to Schindler’s eager embrace of the West’s natural environment and its attendant Edenic mythology, Brecht would interpret LA’s nature as artificial, suspect and ultimately corrupt. “I feel as if I had been exiled from our era, this is Tahiti in the form of a big city,” he recorded in his journal in August 1941, less than a month after his arrival. “They have nature here, indeed, since everything is so artificial, they even have an exaggerated feeling for nature.”6His LA journal—as well as his LA poetry—chronicles his love-hate relationship with the city’s omnipresent gardens, and his refrains about the city’s desert origins and expensive, piped-in water are constant. Brecht was onto something in his faintly apocalyptic scorn and alarm. “Los Angeles is often said to have two seasons: fire and flood,” as the Los Angeles Times succinctly put it in 2005. (Or as the writer Andrew Hultkrans asked a decade earlier: “What is it about this town that makes it such a primary source text for pre- and post-apocalyptic urban environments?”)7Though Brecht never recorded being witness to LA fire or flood, he did note the landslide in the garden of the British actor Charles Laughton, his friend and collaborator on the play Galileo. He memorialized Laughton’s fallen garden in the poem “Garden in Progress,” noting, with sincerity rather than sarcasm, “Alas, the lovely garden, placed high above the coast / Is built on crumbling rock.”8

Brecht appeared to be forever alert to foundations—be they natural or political—and the way they could crumble at a moment’s notice. But his disenchantment with the landscape of his American exile should be seen in a larger context. From his years on the run, nature and society had become constant companions to militarism and war: “Fog envelops / The road / The poplars / The farms and / The artillery,” balefully asserts the poem “1940.” Moreover, in his famous poem “Of Poor B.B.,” Brecht declares that though he might “come from the black forests,” his mother carried him “into the cities / When I was in her belly […] / The asphalt city is my home.” Later, his poem “Concerning the Label Emigrant” seemed to be a sign that LA should not take it personally: “Not a home, but an exile, / Shall be the land that took us in.”

The land that took him and his family in, specifically, was San Pedro Harbor, where his ship, the SS Annie Johnson, departing from the Eastern Russian port city of Vladivostok, landed on July 21, 1941.9As his journal notes, Marta Feuchtwanger, wife of the exiled novelist and playwright Lion Feuchtwanger, and Alexander Granach, an actor, met Brecht and his family at the pier. The transition was not an easy one, and it was made worse by the immediate death of Brecht’s lover and collaborator Grete Steffin, whom he had just left in Moscow, and of his friend Walter Benjamin in Spain.10Despite these tragedies, Brecht attempted to settle in, which in LA meant and continues to mean starting a screenplay. His first idea for a film was to be called “The Bread-King Learns to Bake Bread.”11A socialist-leaning drama about bread making (you can’t make this up), it not surprisingly went nowhere. But he kept plugging away in efforts to make much-needed money and keep himself busy while trying to get productions of his plays mounted on Broadway in New York, refining his philosophy of epic theater, writing new plays and following the war’s movements in Europe as closely as possible.

The surreal oddities of Brecht’s daily life in Southern California—and the lives of the other World War II exiles there—were striking. His poem “Summer 1942” delineates the dark incongruities: “Day after day / I see the fig trees in the garden / The rosy faces of the dealers who buy lies / The chessman on the corner table / And the newspapers with their reports / Of bloodbaths in the Soviet Union.”12And his journal, like his poems, gets the ironies down perfectly. He describes how, a year earlier, on October 21, 1941, “In LANG’s villa grown adults, refugees, sit and listen to the British court astrologer (a former novelette writer for the berlin illustrated weeklies), a fat booby who identifies the constellation of stars in may 1940 as the cause of hitler’s victory over france. He gets very angry if anybody suggests that with hitler’s superiority in tanks and planes april or june would probably have done just as well.”13

A photograph exists of the actor Peter Lorre, Brecht’s close friend, sitting in a garden, wearing a jacket with some floral pattern, reading Brecht’s poetry collection Svenborger Gedichte (the Svendborg Poems, written during his previous exile in Scandinavia). Lorre’s heavy-lidded, inimitable face, so famous from his eerie and extraordinary turn as the child murderer in Fritz Lang’s M, looks strangely out of place under the Southern California sun, Brecht’s poetry in his hands. The image is echoed in photographs of Brecht himself from this time, with his closely cropped hair and baggy, proletariat clothing, his slight body hunched against the LA landscape, signaling some profound discord, a cigar often in hand.

Even as Brecht began to settle in, the contradictions of his existence remained innumerable, with a constant stream of astrologers and set pieces, all the more surreal for being true, like this: “I sent a piece about Hitler to Reader’s Digest (sales 3.5 million) for their series ‘my most unforgettable character.’ It came back very promptly.”14And on May 28, 1942, he recorded:

With LANG, on the beach, thought about a hostage film (prompted by heydrich’s execution in prague). there were two young people lying close together beside us under a big bath towel, the man on top of the woman at one point, with a child playing alongside. not far away stands a huge iron listening contraption with colossal wings which turns in an arc; a soldier sits behind it on a tractor seat, in shirtsleeves, but in front of one or two little buildings there is a sentry with a gun in full kit. huge petrol tankers glide silently down the asphalt coast road, and you can hear heavy gunfire beyond in the bay.15

The incongruity of this scene—of two very different worlds, the old and the new, war and its filmed illusion, crashing together like waves on that beach—startles me. How strange the image of Brecht with Lang (who had fled Germany in 1933) sitting in the sand in Santa Monica, discussing a hostage film. Moreover, the film was to be based on the attempted assassination, just the day before, of the infamous Nazi officer (and one of the main architects of the Holocaust) Reinhard “the Hangman” Heydrich, the Reichsprotektor of Prague. Heydrich would die of his wounds a few days later, and Brecht and Lang would read about it in the Los Angeles Times. And while they were reading that article in sunny Santa Monica and formalizing a film story, Hitler would retaliate by instigating a famous massacre in Czechoslovakia, murdering more than 5,000 people and razing an entire Czech town to the ground.16

Poster for Hangmen Also Die, 1943.

If the image of the overly affectionate couple on the beach strikes me as familiar from my Venice Beach upbringing, the “heavy gunfire” in the bay seems to me shocking; I can’t imagine it, not in that silent, blue body of water along which I grew up. But by 1942, the US and Japan were at war, and American battleships ran daily exercises in the Santa Monica Bay. In any case, the idea for the film would in months become a manuscript and very quickly after that a film directed by Lang: the anti-Nazi thriller Hangmen Also Die. If the process of writing the script and making the film was disillusioning to Brecht, who was stripped of the script credit by an unscrupulous co-writer, it brought him enough money to turn to his plays and poetry, which he produced with astonishing efficiency.

Hanns Eisler, Brecht’s fellow exile, wrote the music for Hangmen Also Die (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award). Brecht’s Hollywood Elegies also were written with Eisler in mind, as six short lyric poems that Eisler could set to music for his Hollywooder Liederbuch (Hollywood Songbook).17The first mention that Brecht makes in his journal of the cycle of poems comes on September 20, 1942.

[Hans] Winge, who comes up to visit me at least once a week from downtown, where he is working in an underwear factory, reads a few of the HOLLYWOOD ELEGIES which I have written for Eisler, and says, “it’s as if they have been written from Mars.” We discover that this “detachment” is not a peculiarity of the writer’s, but a product of this town: its inhabitants nearly all have it.18

Perhaps, but the “detachment” they speak of has often been leveled as an accusation at Brecht’s writings and his person (so much so that James K. Lyon’s indispensable Bertolt Brecht in America includes a chapter called, deadpan one hopes, “Brecht and Feelings”). Brecht wanted his writing, both theatrical and poetic, to engender critical thinking; he despised the hypnotic illusionism and escapism that is Hollywood’s central tenet. Regardless, his critical remove is the perfect foil to lyric poetry’s ecstatic excesses; the combination in the Hollywood Elegies (and his larger body of poetry) produces a near-classical elegance. In a talk written by Feuchtwanger—fellow exile, collaborator, and friend—in 1958, for a BBC program on Brecht, he said:

Story, plot, continuity did not matter to him: what mattered to him, was the right situation, the right gesture, the right word. He visualized the gesture, out from the gesture grew the word, and out of the word grew the character … the word had to be light and elegant. ‘Elegant’ was a favorite adjective of his.19

Even though Feuchtwanger is speaking to Brecht’s more famous theatrical writing—the “epic” plays that indisputably altered 20th-century theater—his description of Brecht’s idea of “the word” is just as applicable to his poetry. The expert elegance of Brecht’s poems about LA lift them from being merely scathing or slanderous. (As Brecht notes acerbically in another poem: “The police forbade lampoons, compelling / Those with a grudge to develop / An art more noble and air it / In lines more subtle.”)20Furthermore, like Brecht’s life in LA and perhaps LA itself, these poems have a dark, incongruous beauty. One can love Los Angeles and love the poems as well; one can love the LA they depict, not because it is admirable, but because it is true.

In Hell too

There are, I’ve no doubt, these luxuriant gardens

With flowers as big as trees, which of course whither

Unhesitantly if not nourished with very expensive water. And fruit markets

With great heaps of fruit, albeit having

Neither smell nor taste. And endless processions of cars

Lighter than their own shadows, faster than

Mad thoughts, gleaming vehicles in which

Jolly-looking people come from nowhere and are nowhere bound[…]21

My pull toward Brecht’s Hollywood Elegies and his California poems, of which there are hundreds, is simple and strange. In a kind of reverse of the path that Brecht and so many of the German-speaking exiles took during the 1930s and ’40s—when they fled Germany first for Switzerland, and then eventually found themselves in New York and Los Angeles—I grew up in LA, moved to New York, and then found myself for some periods in Munich, the city of Brecht’s youth, and then finally in Switzerland, where I now reside. In all this time, the landscape of California had never left my side. Yet here is another surreal incongruity to me, as incongruous as the image of Brecht chilling on the beach: to find the landscape of my childhood in poetry, I had to go back to the Germans. To Brecht, in particular. (Unlike New York, LA does not have a wealth of poetry attached to it; that work has mostly been done by film and fiction.) No matter, then, that Brecht’s Hollywood Elegies are scalding and critical, they also ring true. And the landscape they describe, with its specific images—beaches, oil derricks, tropical trees and flowers, coastal roads, freeways, swimming pools, screenwriters, directors, the glare of sun on stucco houses, the “oily smell of films”—is one whose specificity I feel deeply drawn to and at home in, and can locate nowhere else.

Venice Oil Fields, ca. 1930. Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Libraries Special Collections.

While doing research in Switzerland, I recently came across photos of the Venice Beach oil fields from the 1930s.22By the time I was a child, in the 1980s, these oil fields were mostly gone, but for a solitary derrick lonesomely working next to the old Venice pavilion near our house. Since it was without a pipeline, shadowy trucks would pull up every so often on the beach and cart away its oil to unknown locales. I don’t remember this though, my father had to remind me of it, so I must rely on Brecht’s memorialization of the oil fields in the second and third Hollywood elegies:

By the sea stand the oil derricks. Up the canyons

The gold prospectors’ bones lie bleaching. Their sons

Built the dream factories of Hollywood.The four cities

Are filled with the oily smell

Of films.The city is named after the angels

And you meet angels on every hand

They smell of oil and wear golden pessaries

And, with blue rings round their eyes

Feed the writers in their swimming pools every morning.23

Indeed, B.B