Larry Bell’s Architectonic Light: Early Cubes and Improvisations

by Robert C. Morgan

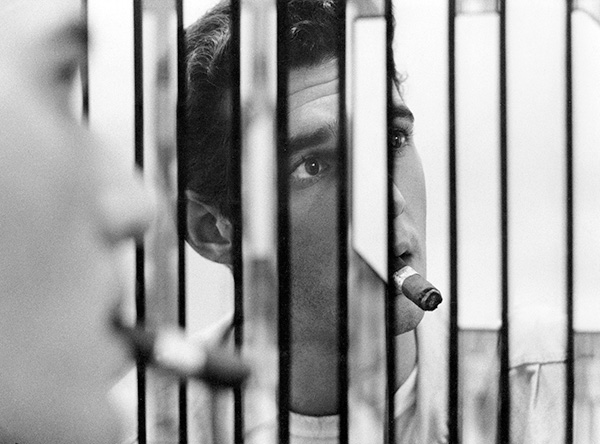

Larry Bell, 1963. Courtesy of the artist.

In 1965, when Larry Bell arrived in New York from Southern California to begin work on the exhibition at the Pace Gallery that would define his career, Minimal art was in full swing. At that time most of the major artists associated with this movement were in New York. The galvanized-steel cubes of Judd, the L-shaped beams of Morris, the die-cut “alloy planes” of Andre, the seriated “structures” of LeWitt, and the fluorescent tubes of Flavin were less concerned with issues of natural light and perception than with primary architectonic issues related to enclosed space. Bell’s concept of designing glass cubes that exemplified transparency instead of opacity opened a point of view as to what Minimal art could be. The atypical positive critical and commercial reception given to Bell’s exhibition at Pace incited surprise and consternation not only among Light and Space colleagues in Los Angeles, including Robert Irwin, Doug Wheeler, and Craig Kauffman, but also among New York artists unfamiliar with his work at the time. In retrospect, one might say that Bell was the first Californian to be given a place within the essentialist New York discourse of Minimal art.1

In spite of his success, Bell felt somewhat bewildered in being associated with the strategies employed by New York artists, whose use of materials and intentions differed widely from his own. As a beach-boy artist fresh from Santa Monica, he was coming from a vastly different point of view, one less concerned with issues of repetition, modularity, seriation, and fabrication than with surface manipulations in which metallic film interrupted the appearance of translucent glass surfaces. In this sense, Bell was doing something quite different from the New York artists. He was transforming cubic forms into vehicles for aesthetic experience, rather than producing reductive industrial entities enshrouded within an impersonally defiant “anti-form” cubic container. For Bell, the process of revealing light, including the translucent flow of light within and through his boxes, offered an expressive feature that was simply not accessible in the galvanized cubes of Judd or the metal plates of Andre or any of the heavy-handed epistemology being used to defend the importance of their art.

Whereas scientists do research in order to establish hypotheses within their respective fields of specialization, artists tend to borrow more readily from fields outside their own. At major university research laboratories, concentrated precision, controlled experimentation, and formulaic objectivity are all essential in determining the outcome of a hypothesis. Despite the intervention of Conceptualism, there is little doubt that the methods of science function differently from those of art; nothing is really proven by artists or by cultural theorists who explicate art as a form of textual illustration. But like science, art is equally limited through choice of material, means of perception, and conceptual language, which are not necessarily exclusive of one another.

Larry Bell, Untitled, 1959. Cracked glass, gold plaint, wood, mirror, 11 x 12 x 4 in. Courtesy of the artist.

For example, in the work of an artist as highly focused as Larry Bell, one is likely to encounter the presence of all three—material, perception, and conceptualization. While one aspect of this triumvirate may be accentuated, the others linger somewhere nearby. The presumed objectivity of his materials is dependent on how form is perceived in relation to its physical and perceptual properties. To conceive of Bell’s work accurately requires sensory data—a visual, haptic, even auditory perception, in some cases. Yet we cannot fully discount the conceptual process that accounts for the work’s presence. Thus, it would appear that the role of the artist is not merely to prove what is shown as art but to transmit its significance in other ways. Within the syntax of material, percept, and concept, Bell’s art enables human sensory capacities to become involved in the related mysteries of light, including the subtle gradations of tone and color. In a statement written for the catalogue that accompanied a recent retrospective exhibition in Nîmes, France, the artist identifies three simultaneous qualities essential to the medium of glass: the transmission, reflection, and absorption of light. He further expresses his move from painting to three-dimensional glass boxes in the early 1960s as offering the viewer a sense of both peripheral and direct vision—something that his earlier expressionist and hard-edge paintings could not do.2

As Bell has made clear in various statements and interviews, this kind of experience or transition in his work happens experientially without the necessity of a predetermined text.3While viewers may note the empirical presence of one of his early glass cubes, he has proven nothing other than to reveal our sensory capacity for light. This may appear relatively obvious, even during the act of perception as illusions of reflectivity become readily apparent. The irony, of course, is that illusions are not concrete facts. They are subject to perpetual change and variation and cannot be easily proven. Thus Bell’s art is less a hypothesis to prove the work’s factual existence than a means to discover its transience as percept measured through the act of seeing in a way that ultimately becomes an acute, unique phenomenon or concept. If I understand the philosopher Husserl’s “phenomenological reduction” correctly, the epoche, or bracketing of a form, is what admits its essence and thereby incites the human potential of being engaged through rarified feeling.4

Larry Bell, Flaw, 1968. Installed at the Palazzo Contarini dagli Scrigni, Venice, 2011. Photo: Angela Colonna and Stefano Ferrando. Courtesy of Foundation 2021, NY.

A recent installation of Bell’s work from the 1960s, situated in the elegant 18th-century Palazzo Contarini dagli Scrigni in Dorsoduro, Venice, suggested a bridge between two time periods, centuries apart from one another.5The cubic ensemble was as much about the concept as about the percept, and as much about material as about abstract form. With a nod toward Husserl, the work engaged both the mind and senses through rarified feeling. Even as the translucent quality of the material appeared in a state of dematerialization, the presence of its form was undiminished. This created a paradox. Were we seeing form through material or material through form? The Venetian light reflecting off the Grand Canal through the high ornate windows of the palazzo transformed this ensemble of six cubes on six separate pedestals into a singular form more than “an expanded field.” The elegant Baroque chamber in which the cubes were placed offered a subtle context that enhanced a feeling of intimacy that further suggested some timeless human potential for heightened sensory cognition, a paradoxical relationship between tactile sensation and virtual reality shown through an unquantifiable angle of vision. While not an exact science, it transmitted a clear phenomenological resonance.

Here one may acknowledge Bell’s intuitive move in the direction of translucency and relative space-time some decades earlier in a frame shop in Venice, California, where he worked assiduously at the outset of the 1960s. One day, while incising a piece of glass to fit a right angle cut, his thoughts began to move outside the frame into a multidimensional void. He built a glass box that contained nothing, because he had nothing to prove. Even so, the existence of the cube felt certain. A sudden absence relieved the agony of the gestural present. The cubic walls of glass took on a shape and meaning of their own. Eventually they would transform into vaporous color and evolve further into a luminous presence and a new language in art. Here, in his own words:

In the frame shop I had access to some wooden shadowboxes and scrap glass and in my spare time I made little constructions with the boxes and cracked glass. I did not know that I would carry on with the glass or the boxes at the time. When I started painting in a studio in Venice, the images were very much influenced by Abstract Expressionism. They very quickly got organized into images of volumes. At some point, I decided to stop painting allusions of volumes and make them instead of painting them. The first works were not cubes but nearly so. Made with wood and mirror, then the cubes emerged, as I wanted everything to be symmetrical.6

As he pursued this work, further practical matters grew in importance, specifically those related to the process of film coating the glass, something he knew very little about at the time. After clarifying his need to do most of the work on the construction of the glass boxes himself, believing that the intimacy of the work space or studio is necessary in order to maintain focus on the work, Bell wrote the following: “In the early days before I had the equipment to do the coatings, I contracted for that service [to Kiem Precision Mirrors in Burbank], but it was way too expensive to experiment with […] so I bought a used coater in New York and got a book called Vacuum Deposition of Thin Films and started on page one. That was in 1965.”7Authored by Leslie Holland, the book was recommended to Bell by Dr. Ben Koenig, a decorative metalizer at the Ionic Research Lab in the Bronx, who opened an important door in the artist’s formative career a few months prior to his opening at the Pace Gallery.8

Larry Bell in his studio, 1970. Photographer unknown.

By 1968, Bell was already moving beyond the objectlike glass cubes occasionally etched with elliptical forms to architectonic glass walls in room-size installations. As Conceptual art was achieving legitimacy and coming more and more into a dialogue with Minimal art, the object began to appear less important than the temporary installation. By 1968, the term “dematerialization” had arrived on the scene, authored by critic Lucy Lippard and artist John Chandler, who advocated the disappearance of the art object in favor of the idea.9 Bell, of course, stayed mostly outside of this dialogue, having returned to Southern California by this time (and by 1973 he had moved to Taos, New Mexico). Even so, his large glass installations, such as Standing Glass Wall at the Vancouver Art Gallery that same year, could be seen in retrospect as another way of interpreting “dematerialization.” The essay by Lippard and Chandler is foggy in terms of whether material can still exist in art even though the object has disappeared, but Bell points directly at the crucial difference between the two. In Standing Glass Wall, as in many other architectonic glass works to follow, the material remains a paradoxically translucent demarcation in which both material and illusion are clearly present. However, the form in the sense of a manageable, easily transportable object has been dismissed.

In comparison with these large-scale glass works by Bell, it is worth mentioning the growing attention given to the dematerialized process works and scatter pieces of Richard Serra at that time. However, it was not until the early 1970s that Serra began deploying large steel plates, thereby bringing opacity back into a post-minimal dialogue with Bell’s translucent plates of glass. For example, it is sobering to compare the complex architectonics of Bell’s 56-piece The Iceberg and Its Shadow (1974–77), which is variable in its “site specificity” according to each location it is placed, with Serra’s more absolute concept of “site specificity” as involving a single location.10In the case of the latter, the resounding argument in relation to maintaining the location of Tilted Arc at the Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan (1981–89) was its lack of permutation.11In view of a comment made by critic Annette Leddy in the Nîmes catalogue regarding the ideological backdrop during the period of the late 1960s when we saw “the movement from a manufacturing economy to a postcapitalist or service economy,” it is interesting to interpret this relative to the manner in which each artist chose to work.12Whereas Serra’s weight and opacity are fixed in time and space, Bell’s fluid, empathetic “improvisations,” carry less weight and announce a more open flexibility. Also, Serra’s gravitational plates of steel appear immutable in comparison with Bell’s transformative sheets of translucent glass. In The Iceberg, the forms never stay the same. The 56 glass components in various shapes and sizes are purposely designed to reconfigure the mise-en-scène according to the architecture of each place.

This was also true of a work of his I saw in 1970 at the Oakland Museum, involving a walk-in glass cubic room partitioned with four diagonal sheets of glass emanating from each corner.13In the center was a small open space for a single person to stand comfortably. In each triangle within the square was a speaker giving a harmonic line that the participant could hear only in that section. To hear the melody one had to stand in the middle where the four parts came together. Bell responded to my inquiry as follows: “The sound piece you mention was an improvisational installation at the Oakland Museum. It was one guitar playing the same two octaves, descending scales but four different sound sources of the same notes started at different times. The sounds all mixed at the center of the room, where a small gap in the wall allowed the sound to mix. I had covered the walls of each of the quadrants of the space with the kind of insulation blankets used on oil derricks.”14

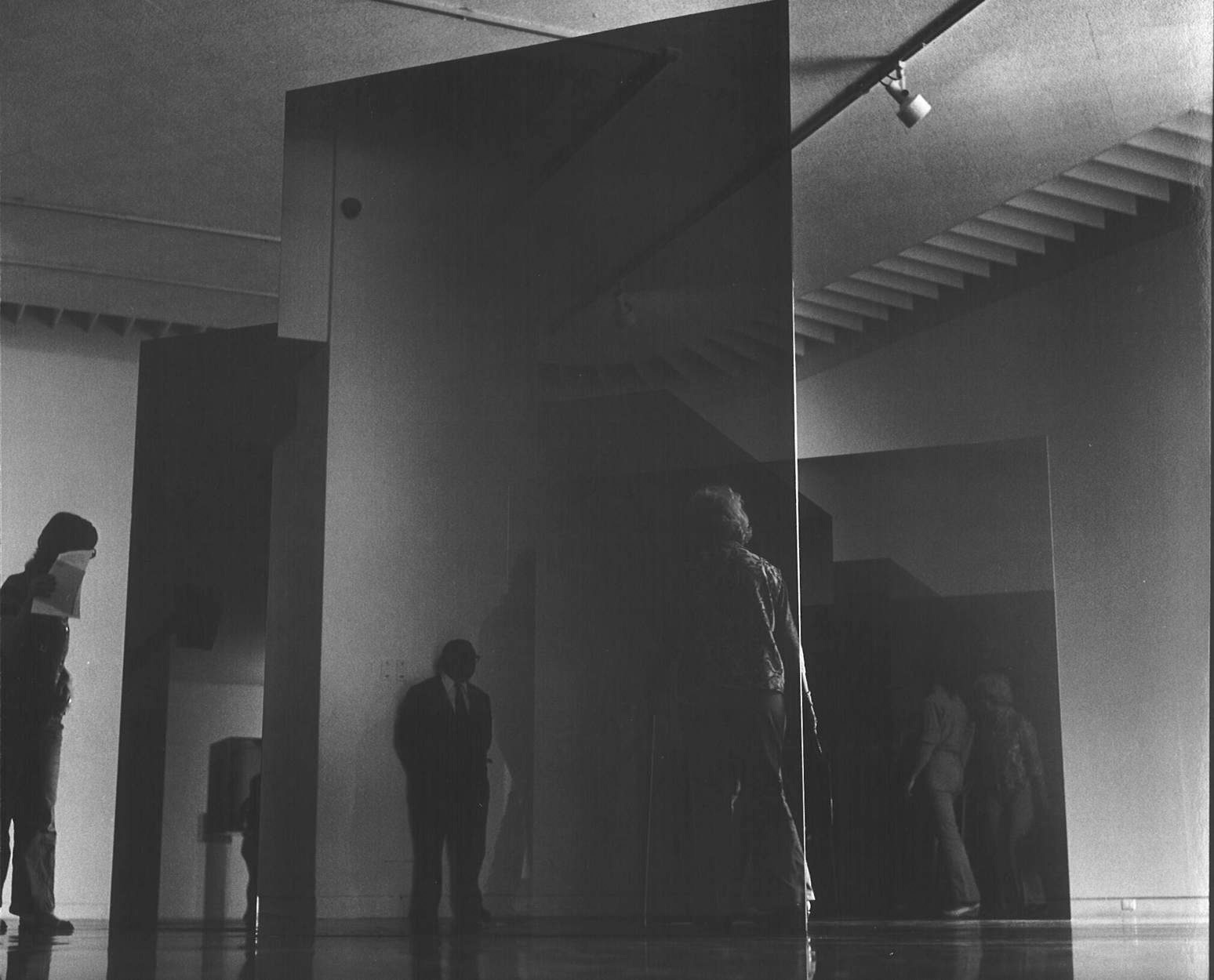

Larry Bell’s solo exhibition at the Pasadena Museum of Art, 1972. Photo: Patricia Faure. Courtesy of the estate of Patricia Faure and the Norton Simon Museum Archives.

The practical concerns for these larger-scale glass improvisations were considerable, namely in knowing that the floor was measurably flat and that the sides and corners of the various parts would match during the process of installing the glass components. This was acutely evident during the installation of Griffin—a work named for the antihero of H.G. Wells’s novel The Invisible Man—in which all of the shapes were hypotenuse right-angle triangles in various sizes. Here, each triangular part was at a right angle that required it be balanced and glued with silicon. Initially, much of the work installing these improvisations was done by Trident Consolidated Industries. They mitered the connections and did the architectural glazing and edging, using the practical industrial standard of ¼ inch. This precision was crucial to the artist; the 24 edges of a large glass cube had to fit perfectly; if they did not, the work lost its authenticity. Bell eventually switched to Bausch & Lomb, who were more expensive but more precise and accurate.15Bell has emphasized that the room-size glass installations had no predetermined idea, a point of view ingrained during his early days as a West Coast Abstract Expressionist painter. Even so, there were always time constraints for the team of workers on the site of an installation that involved measuring, installing, and gluing. Most of the time, the work went smoothly in that the instructions were fairly straightforward. But there were always exceptions that often related to some irregularity in the concrete floor or some other irregularity pertaining to the site.

In the two decades from 1960 to 1980, Larry Bell made extraordinary leaps in coming to terms with the medium of glass—a translucent material that could transmit, reflect, and absorb light simultaneously. Later, he would go on to explore architectonic light through the Vapor Drawings (begun 1978) and the remarkable Mirage Works on canvas and paper throughout the 1980s. In the mid-1990s, Bell accidentally discovered the Stick Figures through a computer program, which later became a series of Sumerian-style icons that recontextualize the posthuman condition. Many of these exist as large, if not monumental, bronzes. In any case, Bell continues to disrupt our predictions and to expand our vision of light and form in cyber-kinetic ways that confirm his preeminent and often polemical role as an artist perfectly at home in the 21st century.