Make Art Not War: Watts and the Junk Art Conversation

by Cameron Shaw

The aftermath of the Watts Riots, August 1965. Photo: Los Angeles Times Staff Photographer. Copyright 2005, Los Angeles Times. Reprinted with Permission.

Only months after publishing The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon wrote an account of life in Watts for the New York Times Magazine.1On May 7, 1966, a Los Angeles police officer had shot and killed Leonard Deadwyler, a black man whose name could easily have been plucked from Pynchon’s novel. Ruled an “accident,” Deadwyler’s death was salt in the wound of a neighborhood still smarting from its last fight with the cops.

In the aftermath of the Deadwyler incident and the subsequent trial, the chaos of the previous summer loomed large in the minds of neighborhood residents, and of those elsewhere via media headlines. Despite a few reports of smashed windows and Molotov cocktails, there was no repeat of what had transpired in August 1965, when, after the public arrest of the motorist Marquette Frye and his family, the area erupted into six days of violence, looting, arson and destruction that came to be known as the Watts riots.

Even without a catastrophic reprise, it would have been difficult to argue that life for the residents of Watts had improved in that year since the riots. As Pynchon pointed out, despite the onslaught of pure-intentioned social workers, data collectors and VISTA volunteers in the area, the problem was much broader than a single episode with Deadwyler or Marquette, or even issues of police brutality or poverty.2The author spoke, as he expressed in The Crying of Lot 49, of a fundamental inability to communicate—this time between black and white cultures. If, as Pynchon—an outsider himself, albeit a highly critical one—noted, “white values [were] displayed without let-up on black people’s TV screens,” what were the available tools for blacks to communicate the realities of their existence?

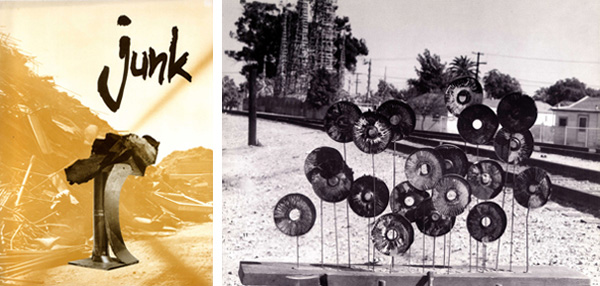

Left: Cover of exhibition catalogue for Junk Art: 66 Signs of Neon, Los Angeles, 1966. Right: Debby Brewer, Sunflowers, 1966. Mixed media. Courtesy of the Noah Purifoy Foundation.

In his article, evocatively titled “A Journey into the Mind of Watts,” Pynchon described the festival as a “restructuring of the riot.” The collaborative artwork was a literal restructuring in that it used the raw materials of destruction to build anew. The Junk Art catalogue that Purifoy and Powell produced in conjunction with 66 Signs of Neon figured an additional valence, imagining the installation as a physical addendum to the McCone report. In the wake of the riots, California governor Pat Brown named John McCone, who had recently stepped down from his position as director of the Central Intelligence Agency, to devise what would seem impossible: an “objective and dispassionate study” that would explain what had occurred on the streets of Watts, outline the causes and suggest potential remedial actions. The report, known formally as “Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning?” made plain what many already knew: the people of Watts, like many predominately black communities across the nation, were facing joblessness, a dearth of affordable housing, and insufficient schools.6Purifoy and Powell, however, found a critical component to be missing from the report: creativity. They believed art and art education to be among the most important resources available, especially for young people, specifically because art could transform consciousness. Through 66 Signs of Neon, the artists were then calling for more than a restructuring of physical materials; they wanted a restructuring of values.

If creativity was, as the artists suggested, the key to self-development, then they planned to lead by example. Through 66 Signs of Neon, they proved how little was required from the external world to manifest creativity. While the use of found objects was not new in an art context elsewhere—from the contemporaneous junk art Edward Kienholz was making just a few neighborhoods away, to the Arte Povera movement gaining momentum in Italy—this was a potentially life-altering idea for a child in Watts whose family was struggling to make ends meet. He could, in essence, use any and everything around him as fodder for new creation.

According to a checklist from the Noah Purifoy Archives at the Noah Purifoy Foundation in Los Angeles, there were roughly 50 works for sale that composed 66 Signs of Neon, 15 of which were illustrated in the Junk Art catalogue. In the New York Times Magazine, Pynchon describes one work that does not appear by name in either the catalogue or checklist:

In one corner was this old, busted, hollow TV set with a rabbit-ears antenna on top; inside where its picture tube should have been, gazing out with scorched wiring threaded like electronic ivy among its crevices and sockets, was a human skull.7

Poetically, Pynchon suggests a name for the piece: The Late, Late, Late Show, thus the foil of his thesis that white America communicates its culture to black America via the television set. The transmogrification of the object then makes possible the response: “here is an expression of our reality.” The object becomes a symbol of the one-to-one communication the artists so ardently advocated. They hoped that this conversation between individuals facilitated by the art object would be carried far beyond Watts. Purifoy wrote a letter before the show began, inviting “a small group” of people in Los Angeles, presumably those he thought had either money or clout, to come see the show and potentially facilitate its travel to other venues. The work did end up traveling throughout California—to nine state universities, where it was, tellingly, shown in the student unions rather than the art galleries—and eventually made its way throughout the United States. It met with mixed responses, from “Scrap metal salad. Shredded newspapers. 400 frenzied orangutans hurling paint cans. Demented junkman’s paradise” to “The highest form of the artistic spirit is here in abundance.”8

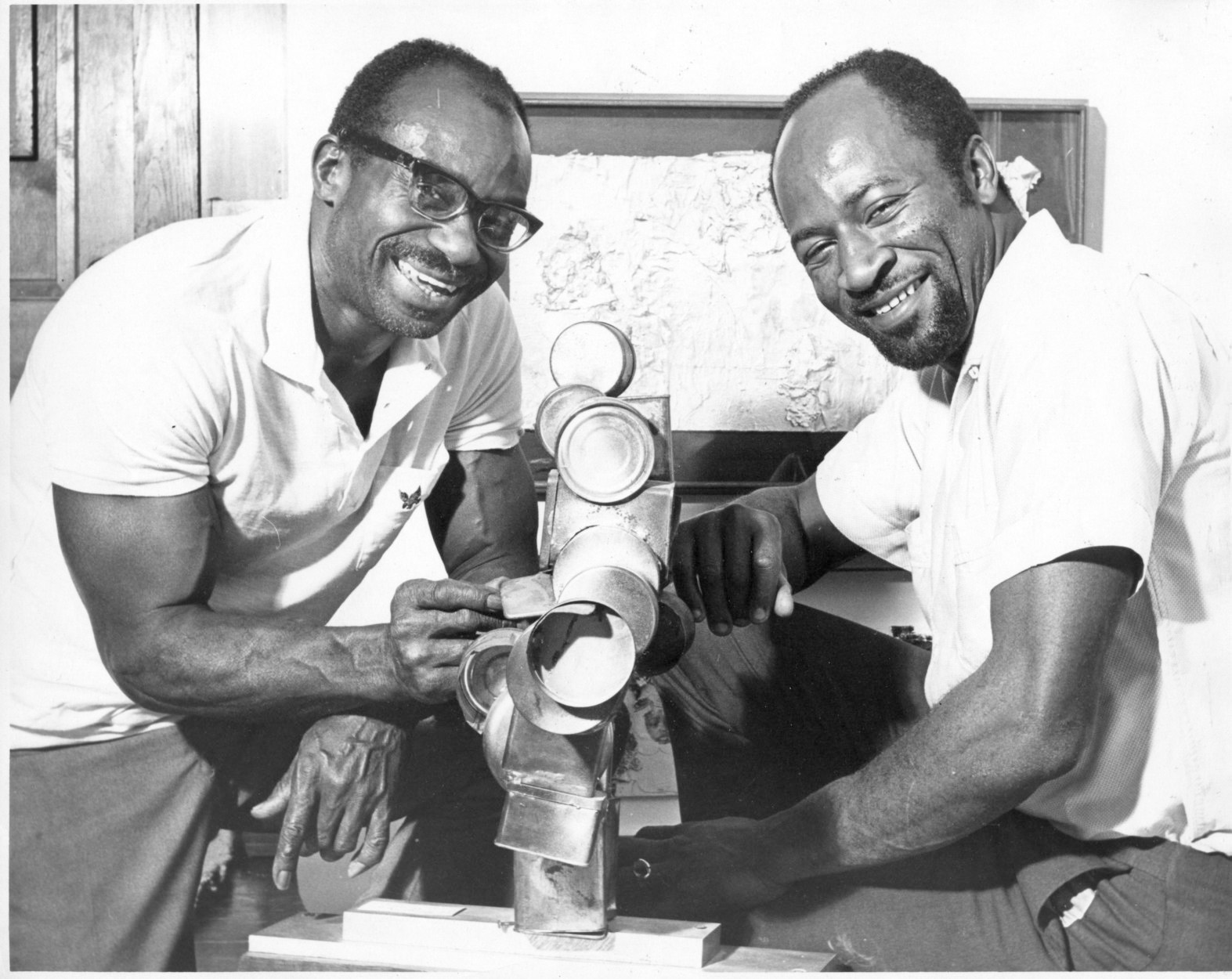

Noah Purifoy and Judson Powell at the Watts Towers Art Center, Los Angeles, ca. 1964. Courtesy of the Noah Purifoy Foundation.