Mythology and the Remake: The Culture of Re-performance and Strategies of Simulation

by Jenni Sorkin

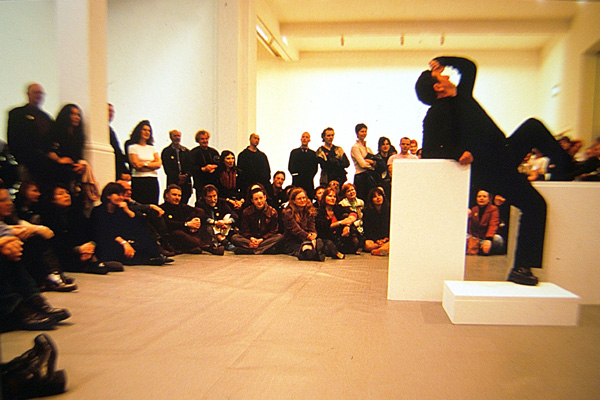

Bruce McLean, Pose Work for Plinths, 1970/2002. Performance in “A Short History of Performance,” at Whitechapel Art Gallery, April 20, 2002. Courtesy of Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

For many years now, performance art has been, for the most part, enlivened, heightened and disseminated through its retelling in various exhibition catalogs, museum object labels and scholarly publications. This changed at the millennium: compelled by the new century and the perception of historical distance, “re-performance” became, for some museum curators, a thrilling idea. In April of 2002, the Whitechapel Gallery in London offered one of the earliest ventures: a series called “A Short History of Performance Part One,” in which works by Carolee Schneemann, Stuart Brisley, the Kipper Kids, Hermann Nitsch, Bruce McLean and Jannis Kounellis were restaged to praiseworthy reception. Of the event, Rachel Withers wrote in Artforum: “A Short History” may have ‘repackaged’ some key performances, but in doing so it mapped the crucial interplay between performance and memory, an undeniably fascinating process.”1

Thus began an era of simulation, culminating in the icky sensationalism surrounding Marina Abramovic’s re-performances and perpetual presentness at the Museum of Modern Art in New York this past spring. In the mainstream and art press alike, much was made of the naked reenactments of her 1970s- and 1980s-era performances, which, according to the New York Times critic Holland Cotter, were initially premised on a credo that was anti-repetition: “no rehearsal, no predicted end, no repetition.”2Clearly, this is a bygone ethos in the artist’s oeuvre. In restaging an entire exhibition of re-performances with other, younger performers, ego became the blunt driving force propelling the enterprise. So what, then, is the relationship between re-performance and self-parody?

Like Abramovic, most early performance artists rejected theatricality and, in doing so, rejected the revivalism inherent in narrative—that which makes it possible for a story to be resuscitated again and again. Performance art was live, often performed just once, sometimes in the privacy of the studio, sometimes for an audience of peers or for the anonymous public. Often, a kind of heightened ridiculousness prevailed: Bruce Nauman bouncing his testicles on camera, or VALIE EXPORT offering her naked breasts to random strangers. The presumed authenticity of these gestures—that all these works indeed can be ascribed a legitimate political efficacy, usually as a form of social commentary—is by now assumed. Using the body as an artistic tool, the artists became subjects, literally subjecting themselves, for better or worse, to elicit some sort of social response. Remake such works now, in our current era of reality television and all-access excess, and the social commentary will likely get lost, or prove impossible to distinguish from an uncritical climate of permanent outrageousness where the televisual body is always sexualized, gendered and raced. This is why, for instance, Vanessa Beecroft’s performances from the early 2000s—in which corps of silent, nude models in stilettos graced the foyers of museums worldwide—have fortunately died out. They were late to the party and ultimately trite; a culturally sanctioned version of, say, America’s Next Top Model, minus all the clothing.

Yet most of the avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s was steeped in contrasts: even if the work was performed only once, it was still extensively documented. Though it often seems that these documentary “texts”—film, video, sound recordings, photographs, diagrams, descriptions, drawings—were made casually, without the vainglorious professionalism characteristic of today’s MFAs, there is simply too much of it to ever seem truly casual. Rather, it seems the mark of commitment to the daily practice of being an artist in the era that preceded the digital revolution. This generation of practitioners is always assumed to be anti-object, but being process-based is not synonymous with a lack of objects. These text-objects must have been created in order to extend the aura of the singular performance, compounding the work’s aftereffect and adding a rich layer of detritus through which we can now sift.

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy, 1964/2002. Performance in “A Short History of Performance: Part One” at Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, April 16, 2002. Photo: Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist.

So let’s make another assertion. Through its continual circulation in the form of documentation, the performance’s aura may well be extended—even commodified as a distinct form altogether, as Carrie Lambert-Beatty has recently pointed out—but it cannot be divorced from the original action, which was particular to its original, often colorful circumstances.3

On February 17, 1976, the artist Kim Jones, a Vietnam veteran and a recently minted MFA, smeared mud and feces on his naked body and stretched a nylon stocking over his head to effect a kind of camouflage; then, in an act of protest against the brutality of the war, he burned four live rats at the Cal State Los Angeles student union art gallery, in the controversial performance that came to be known as Rat Piece. The student and community outrage grew to mythic proportions: legal action was taken—Jones was formally charged with cruelty to animals—and within the month, the gallery’s director, Frank Brown, was fired after defending the work as an “aesthetic sacrifice.”4Never repeated, the work came to be well-known through its retelling: the word-of-mouth testimonial repeated by people who had seen the work, and those who had not but felt compelled to narrate the performance, or perhaps a wrongful version of it, over and over. Never mind that there is some blurry photographic documentation of Jones’s piece. The documentation itself is a secondary act. Unlike the Abramovic-style restaging, which becomes, like it or not, a form of visual theater, the continual narration of Rat Piece becomes its own form of testimony. And not always firsthand. In the retelling, the action is always at least once removed, reproducible as an oral tradition, preserved and reanimated by the fact that the new receiver uses his or her own aural faculties, intuiting the action through hearing and perceiving rather than simply seeing. In this way the action comes to inhabit the receiver’s imaginary. Like the children’s game known in some parts of the world as “Chinese whispers” and in the US as “telephone,” the original whispered phrase becomes increasingly degraded, and oftentimes completely misconstrued, as it makes its way around the circle. Such errors of transmission—which can also obscure the sincerity of artistic intent—are the simple pleasures of experiencing performance second- or thirdhand. The mythology of the piece exists, and its retelling is an opportunity to reinvigorate the original work of art. Or even reinterpret it altogether, this time, maybe, with a little hilarity. Of Interior Scroll (1975), Carolee Schneemann has recounted:

Really, I prefer to describe it incorrectly. I had an interview with a Danish art historian and she wanted to focus intensively on that piece. And she kept saying how much it must have hurt. And I said no, it doesn’t hurt because the material is folded up, in a kind of origami, and then very nicely oiled. “No, no,” she said, “but really, it had to hurt.” So we were at this impasse. I kept saying, “No really, I don’t do works that are about pain or the abject.” She insisted: “But the interior squirrel, their claws!” That’s the best mis-interpretation. 5

Rather than trying to resurrect past works, as though performance art were the same as dance or theater, we might be better off allowing them to loom large historically, and continue on as ghosts that haunt contemporary practice. If we could embrace the literal mythology of avant-garde performance and think of it as a collection of stories—think of its ascension as an oral, rather than a visual, tradition, and as one that accrues significance in its retelling—the legacy of 1960s- and 1970s-era performance art would sustain itself without the disappointment (and low ticket sales) inevitable in the remake. My proposal is simple: take the work out of visual circulation. This doesn’t mean stop showing the photodocumentation in museums or lecture halls. Quite the opposite. But the photos (or videos) do not speak for the work. The work itself demands speech, retelling, converting what was once visual/visceral into a narrative account. For instance, who doesn’t want to feel a little accosted when being told about Vito Acconci’s Seed Bed (1971), in which the artist erected a ramp and a little more (!) in a SoHo gallery, masturbating beneath the structure, while shocked gallerygoers strolled overhead, listening intently to his spoken-word fantasies and bodily noises as the artist achieved “his crisis,” as D. H. Lawrence used to call it? Even the squeamish can take refuge in a little comic relief: a recounting, in turn, of Susan Mogul’s video parody, Take-Off (1974), a feminist response to Acconci’s cumulative works, in which the artist, facing the viewer, talks directly to her audience while masturbating with a vibrator beneath a kitchen table.6Then the works will live on in tandem, self-assimilating as a kind of call-and-response, enlarging the infamous, but narrow, canon of extreme performances, those by Chris Burden, Otto Meuhl, Nitsch, Gina Pane, and Schneemann.

Some of these works—such as Burden’s Shoot (1971) or Pane’s L’Escalade non-anesthésiée (1970) do have residual documentation—Burden’s sound recording; Pane’s ladder with glass shards, on permanent display at the Centre Pompidou—but for the most part, these works have gained a currency, and indeed, a full-blown mythology surrounding them, from their word-of-mouth circulation.7That is, their reception is neither static, nor confined to their own time and place. Rather, the works continue to captivate an audience that has never seen or experienced, and more importantly, will never see or experience, the original work, or perhaps even its documentation. The accretion of an audience—through casual retelling, through scholarly lectures, through writing and reading, is what allows the work to ripen, and offers the potential for multiplicity in interpretation and in criticism—the artist can seem both radical and naïve, rather than one-dimensionally heroic or tragic. This is precisely why art historians like to rework Warhol and Cage: because such a substantial body of work on both already exists, and it is worth reconfiguring and recontextualizing for each subsequent generation. My Warhol is not John Giorno’s insecure, genius Andy, but he is not Jennifer Doyle’s queer dandy, either. My Robert Morris is not Krauss’s—or something like that. After all, isn’t he just the theoryhead who hooked up with all the feminists? The amazing thing to me is the ability to create a contentious ownership, in which this kind of flippancy is only possible because we all admit to Robert Morris’s justifiable importance—we’ve all read Notes on Sculpture, and we get it, so let’s build on it, and rework Morris’s own legacy in relation to his specifically female peer network: Schneemann, Yvonne Rainer, Lynda Benglis.

Kim Jones, video stills from Rat Piece, 1976. Performance at Cal State, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist and Pierogi, Brooklyn.

Like a vintage wine, surely performance grows in spectacle as time goes on, but it also acquires a maturity and depth as well, and a sheen of age. Via oral narration, the myth itself is altered continually, to allow the voice of the narrator—the storyteller—to adjust accordingly: to add, blend, exaggerate, or reconfigure entirely. Rather than reach for painstaking accuracy in the restaging, it seems far more preferable to admit that the historical specificity of the performance’s original moment is indelible: the ink allows us to read through the work itself, while making room to write over it, as Mogul did to Acconci.

The literary scholar and Jesuit priest Walter Ong’s important book Presence of the Word (1967) offers a theory of the way in which the speech act is spread through its auditory and kinesthetic (the perception of motion) properties. Ong emphasizes the dependency of the “oral-aural” tradition for the circulation of important cultural and religious ideas. His theory was that in preliterate societies, for instance, medieval Europe, or in colonial societies, the Bible functioned as an aural medium in which the word, the Gospel, was transmitted aurally—through listening, rather than through the self-education of reading. Bible stories were subsequently reinforced through art (paintings, murals and devotional objects) and theater (Passion plays). In a highly literate society such as ours, sound is increasingly a disembodied abstraction that is hopelessly mediated (see the ubiquitous iPod or Bluetooth device), further distancing us from our past historical methods of transmission: storytelling.

Ong was, not uncoincidentally, one of Marshall McLuhan’s early mentors, no doubt contributing to McLuhan’s own theorization of the circulation and reception of media culture. Like McLuhan, Ong believed that new aural technologies—then, the telephone and television—manifested new avenues for the potential of reinstating a tradition of touch, or recouping the literacy of feeling found within the spoken and performed transmission of culture. Reapplied to performance art, Ong’s ideas challenge the contemporary commonplace belief that visual documentation, and with it, the live remake, is the best means of preserving performance history. Rather, an oral-aural tradition—no longer in favor—is what actually encourages true acts of transmission, beyond mere spectatorship.

In our current culture, the remake has become especially prevalent in mainstream film and television culture, remaking old TV series (Hawaii Five-O, Beverly Hills 90210, Star Trek and the like). This lack of invention is purposefully lowbrow, giving the masses what they really want, a slicker version of the familiar, rather than forging new ground. Is this really how we want the avant-garde to turn out too? Restaging is fast becoming the norm, a way for once anticommercial artists to capitalize on their old successes, appeal to a new generation, and revisit vital moments in their career. Will museums, short on cash and in desperate need of higher attendance records, add “re-performance” to their line-up, now that MoMA hit the jackpot with Marina?

“Joint Dialogue,” an exhibition of old work by Lee Lozano, Stephen Kaltenbach and Dan Graham, curated by Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer at Overduin and Kite in Los Angeles this past January included a re-performance of Dan Graham’s Lax/Relax (1969). But the boredom is apparent in watching the clip I saw online.8In it, the audience spends more time angling for space in the cramped room, and cruising the room to see who else is in attendance—than watching Graham. So much for legendary performance. But it is more than likely that Graham’s original audience felt the same way—boredom was a crucial feature embedded into the structure of first-generation performance art. Many of Chris Burden’s pieces, for example, test either the artist’s or the audience’s endurance. Much of first-generation performance art did not pander to its audience: in many cases, it was openly hostile to the audience, or disengaged from one altogether, with the artist performing alone, as in Chris Burden’s Locker Piece (1974), which could only have been made before our contemporary era of heightened security, ID swiping, and camera surveillance. To my knowledge, no one has ever stated a desire to remake the work in which Burden occupied a locker for a week, drinking from water stored in the locker above him, and pissing into a container stored in the locker below. One doesn’t need to look at anything to enhance the retelling, and you don’t need photos to understand the work. Hearing its conceptual premise is more than enough.

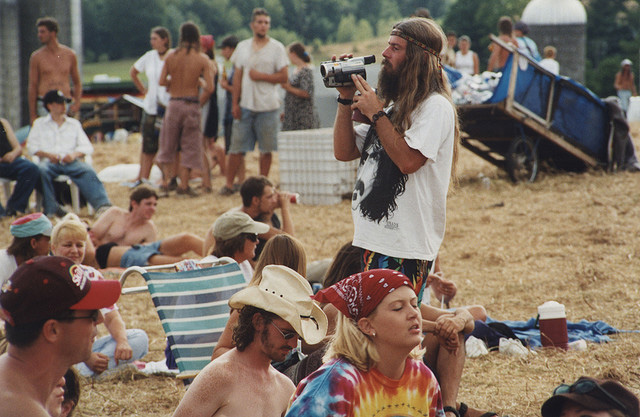

30th anniversary of the Woodstock Concert, 1999, Woodstock, NY. Photo: Chris Conroy.

Restaging is actually a form of sublimation: a purposeful forgetting of the initial intentions of an entire generation (Abramovic and her ego notwithstanding), and as well, a simulation of an anticommercial, preconsumerist culture. And what is simulation but a kind of yearning for simultaneity—the nostalgia of wanting to have experienced it firsthand? Amelia Jones indexed this feeling theoretically, in 1997, discussing the haunting of performance art “in absentia”:

I was not yet three years old, living in central North Carolina, when Carolee Schneemann performed Meat Joy at the Festival of Free Expression in Paris in 1964; three when Yoko Ono performed Cut Piece in Kyoto; eight when Vito Acconci did his Push Ups in the sand at Jones Beach and Barbara T. Smith began her exploration of bodily experiences with her Ritual Meal performance in Los Angeles…This agenda forces me to put it up front: not having been there.9