Odd Couple: Yves Klein and Ed Kienholz’s Unlikely Affinities

by Joanna Fiduccia

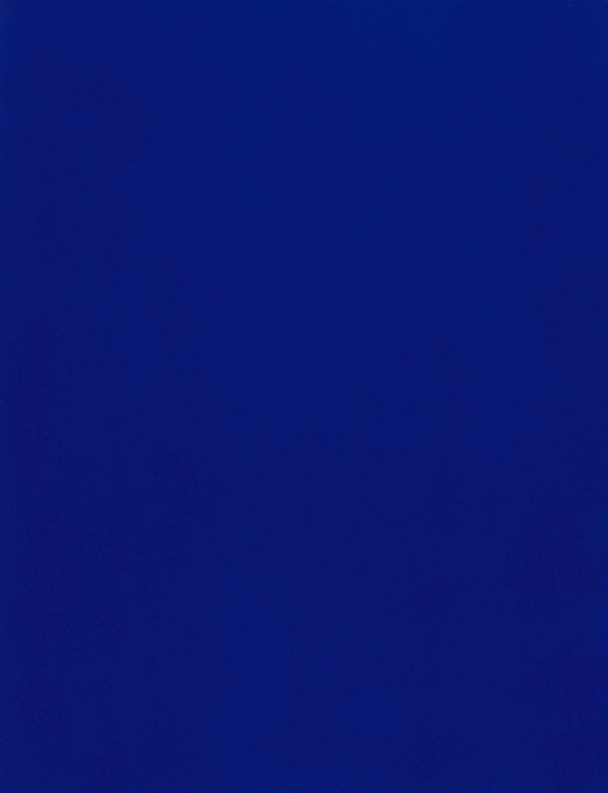

Rotraut Klein-Moquay with part of Yves Klein’s Zone for Edward Kienholz, 1963. All Klein images courtesy of the Yves Klein Archive, Paris.

Shortly after the untimely death of her first husband, Rotraut Klein-Moquay set out to sea carrying a box of gold leaf. A photograph from that afternoon shows the widow shaded by a sun hat, cradling the gold in her lap just minutes before she and her companion on the trip, Yves Klein’s oldest friend, Arman, would scatter it into the Mediterranean.1Despite the circumstances—Klein’s sudden expiry, the reunion of the mourners who seemed to cast into the waves the remains of the lost art phenom, transmuted into the remnants of his gold monochromes—there was nothing lugubrious about the ritual. In fact, its purpose wasn’t even to honor the deceased, but rather to honor an exchange with one of his acquaintances, many miles away in Los Angeles—the artist Edward Kienholz.

A year earlier, when Yves Klein and his wife arrived in Los Angeles following a short stint in New York, Kienholz had greeted the famed French artist with a welcome gift: a briefcase outfitted irreverently with certain items including a bottle of “GoodAire,” a blue-pigment-soaked sponge, and an aerosol can labeled “IKB” (for International Klein Blue). Amused by the gesture, Klein offered Kienholz in return a piece of the Void, one of a series of Klein’s works known as the Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility. This plot of nothingness constituted a heightened state of sensitivity, which Klein typically exchanged for a given weight in gold; but its full transfer could only be completed if the buyer agreed to burn the receipt of purchase (thus leaving no material proof of ownership), at which point Klein would throw half the gold into a river or ocean.

Rotraut Klein-Moquay getting ready to scatter Yves Klein’s Zone for Edward Kienholz, 1963.

Most accounts of the Zones include only those ritual relinquishments that took place on the banks of the Seine between the years 1959 and 1962, neglecting this posthumous transfer undertaken for Kienholz by Klein-Moquay and Arman.2The ritual for Kienholz was an anomaly in several ways: its high officiator had departed, its beneficiary was 6,000 miles away, and its gold was not the purchase price paid by a collector, but a proxy for his gift. Finally, although Klein had exchanged a number of works with other artists during his stay in the United States, Kienholz was the only one to get a Zone.

Why Kienholz? Or for that matter, why Klein? In the early sixties, Kienholz’s work seemed much closer to that of their mutual friend Jean Tinguely, and one might imagine that Klein’s taste for showmanship would have made him “too Hollywood” for Kienholz or anyone in the Los Angeles art scene at that time. Yet Klein certainly had something that captivated Kienholz then, even if it took several years to appear on the surface of his works; something that complemented what the West was and was to become—its vast spaces, its fast money, its dark armatures.

Klein came to Los Angeles in 1961 at the behest of Virginia Dwan. Best known as an instrumental advocate and sponsor of Land Art, Dwan was also the key proponent of Nouveau réalisme on the West Coast. In the early sixties, she was a young dealer of considerable ambition and means. Enthusiastic about European art, she single-handedly provided a generation of local artists with references that extended beyond New York, with works by Klein, Arman, Martial Raysse, and Tinguely all appearing in her gallery during those early years. As Kienholz himself testified, “Virginia Dwan was responsible for the whole influence of Europeans on the West Coast”—starting with that of Klein.3

Klein had already been in the States for a couple of months, which he had spent preparing for his exhibition at Leo Castelli in New York. Klein had arrived expecting an American coup, but unfortunately, the trip was not the success he had hoped for. Critics panned the Castelli show, finding in it nothing but charlatanry and froggish bluster; in Art News, Jack Knoll cuttingly called him “the latest sugar-Dada to jet in from the Parisian common market.”4Artists meanwhile were put off by Klein’s abrasive mix of hierophantic rhetoric and hubris, and most painfully, Klein’s great hero Rothko rebuffed him, leaving Klein brooding and bruised, and eager to continue west.

For the Kleins, then, Los Angeles meant an escape from New York and its disappointments. Los Angeles was milk cartons and sliced white bread, sailboats and sunshine, Disneyland and Death Valley.5It was a place that resembled both the Nice of

Yves Klein, California (IKB 69), 1961. Pure pigment with synthetic resin on gauze mounted on board, 76 x 55 in.

Yves’ youth and the platform of the future, a glamorous town where people sunned themselves during endless boozy afternoons, talking openly of money—much to the shock and awe of Rotraut. As she recalled, “Here art had one value: the dollar, and more importantly, the purchase price.… Today I realize our ignorance of this culture, which was thirty years ahead of our old France.”6Negotiations over the purchase of artworks were discussed with the kind of detail one might lavish over the surface of a painting. It held the same fascination in Los Angeles that Klein’s 1957 L’Epocha blu at Galleria Apollinaire in Milan had presaged several years earlier: Klein claimed that the exhibition, in which he displayed—and sold—11 very similar blue monochromes, all with different price tags, proved that pictorial quality could be based on something other than material and physical appearance, something he called “pictorial sensibility.”7For Klein, pictorial sensibility, the “indefinable” of art, was no less than “the barter price of the universe of space,” the means by which “we are able to buy life.” In Los Angeles, a culture already expert in selling life through lifestyle, sensibility’s purchasing power not only seemed reasonable, it was gospel.

While still in New York, presumably licking his wounds at the Chelsea Hotel, Klein drafted his “Chelsea Hotel Manifesto,” an English-language primer on his oeuvre that, given the circumstances, reads as an apologia as well.8In it, Klein announces his interest in “the corney [sic],” motivated by his sense that “there exists in the very essence of bad taste a force capable of creating something far beyond what is traditionally termed art.” If so, in Los Angeles he had landed in the right city; the best Hollywood directors had been plumbing just that premise for a couple of decades already. As Robert Pincus-Witten explains in his book on Klein’s American sojourn, Yves Klein: USA, “Klein, in short, [was] trying to isolate something that is hard to admit, that authentic art in establishing a new canon need not begin—and probably does not begin—in good taste but rather as an art that is unrepentant and sans apology.”9For someone like Kienholz, who would infamously offend good taste with his LACMA solo exhibition of 1966—the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors called his sculpture Back Seat Dodge ’38 (1964) pornographic and blasphemous, creating a combustible situation for the museum and a frenzy in the press—Klein’s desire to offend with panache and conviction, to exploit sentimentality unrepentantly, must have been alluring.10His exhibition at Dwan Gallery, “Le Monochrome,” opened on May 29, 1961, to an enthusiastic audience. Yves Klein, in Los Angeles, had finally arrived in the New World.

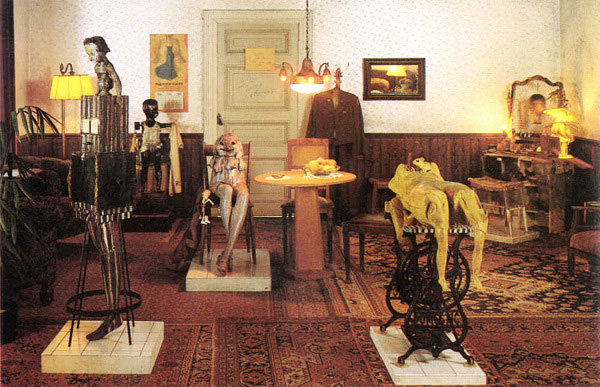

When Klein’s exhibition opened, Kienholz was fully occupied with the construction of Roxy’s (1962).11The most significant of his early tableaux works, Roxy’s was a phantasmagoric (and graphic) re-creation of a Vegas whorehouse, a room-size environment populated by begrimed and mutilated mannequins. Roxy’s typified the tableaux to follow: vivid environments with their roots in social critique, composed from the detritus of that same society—trash and castoffs that Kienholz slowly accumulated and carefully assembled.

Edward Kienholz, Roxys, 1962. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Copyright Kienholz, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, California.

In these tableaux, Kienholz’s association with Tinguely—also working in monumental assemblage, also highly resourceful with a scrap heap—is evident. Yet his environments, all clutter, reference, and barely restrained chaos, couldn’t seem further from Klein’s harrowingly pristine Void.12Whereas curator Pontus Hultén, who would later prove a strong advocate for Kienholz in Stockholm and Europe as a whole, described the tableaux as “traps, a purposely inviting environment that Kienholz entices the spectator into” for the purposes of “mak[ing] his point clear,” Klein’s Void was an intimidating sanctum; it was a theater of presence, not of positions.13Klein’s aim was ambiguous and defined by barriers, from the formal invitation cards to the national guardsmen he stationed at the door to the Void, to the psychological menace some found in an empty space. One man, Klein boasts, trembled at the threshold and could not enter. “I will come back once the void is full,” he called out to the artist, to which Klein replied, “When it is full, you will no longer be able to enter.”14The Void, he made clear, was not a space for political sympathies or, for that matter, much sympathy at all.

Kienholz, on the other hand, continued to make socially critical tableaux through the sixties—including The Beanery (1965), a re-creation of a local dive bar with a pile of newspapers posed by the entrance whose headlines read “Children Kill Children in Vietnam”; and The Portable War Memorial (1968) and The Eleventh Hour Final (1968), which foreground, respectively, the iconography of war and the abstractions of mass media during wartime. Before these, however, he embarked on another kind of tableau, one closer to the spirit of Klein’s work. Called the “concept tableaux” and created between the years 1962 and 1967, these works consisted of plans for large-scale environments whose execution would be undertaken only on the condition of the artist’s finding a buyer, who would also function as their financier. Like the Zones, the rules governing their creation were set out on paper, in a legal document stipulating the conditions of ownership for a concept tableau.

Ownership took place in three stages, necessarily sequential but not necessarily carried to completion. First, the concept itself: a typewritten paragraph describing the tableau—often monumental, fantastic, or otherwise difficult to execute—signed, dated, and thumbprinted by the artist. This was the most expensive part of the piece, typically running between $10,000 and $15,000. The second element, which could be purchased for a much smaller cost ($1,000 in most cases), was a drawing of the concept tableau to be realized. Finally, the third element was the realization of the tableau itself, which could be purchased for the material production costs, plus “artist’s wages”—that is, the fee, plus a reasonable per diem, that Kienholz would demand for his physical labor during the construction of the piece.

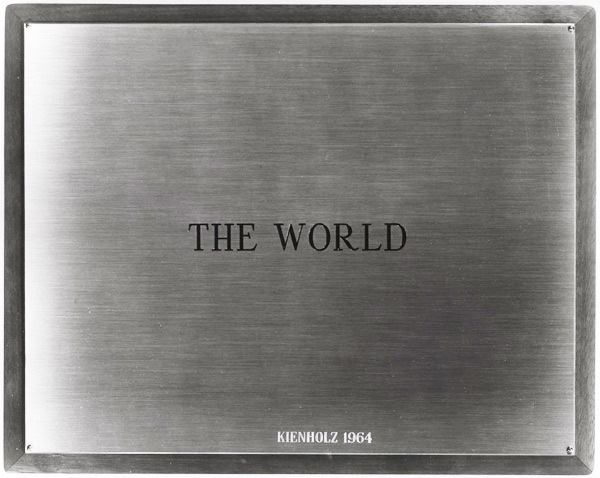

Edward Kienholz, The World, 1964. Concept tableau. Plaque: 9 1/4 x 11 3/4 in. (illustrated). Framed: 13 3/8 x 9 1/4 in. (not illustrated). Copyright Kienholz, Courtesy L.A. Louver, Venice, California.

Certain of Kienholz’s concept tableaux bear a strong likeness to Klein’s work. Cement Store #1 (Under 5.000 pop) (1967), which proposes the encasement of an entire interior of a grocery store in cement, inverts the Void, turning a space of commerce into a concrete—and absolutely impenetrable—object of contemplation.15A tableau from 1964 called The World refers to a particular five-acre plot in Hope, Idaho, on which Kienholz “plan[ned] to sign the world as the most awesome ‘found object’ I have ever come across.… The tableau will be a simple rectangle of concrete, about five feet thick, fifteen feet wide and forty feet long. On the southwest corner I plan to inscribe ‘THE WORLD… Kienholz 1964.”

The concept recalls one of Klein’s origin myths: a day at the beach when he, Arman, and Claude Pascal, three teenage aspirational mystics, divided up the world among themselves and signed their new estates. Yves signed the sky—his first blue monochrome; Arman got the earth. But unlike Klein, who asserted his ownership thenceforth of the wild yonder, Kienholz insists that in his tableau, “I would never attempt such an act for myself alone. I want to be the first of many persons who might care to come to Hope to sign this peaceful corner of the world as a symbolic gesture of true acceptance and reaffirmation of it.” His optimism transports the claim away from Klein’s megalomania to the opposite—but equally unpalatable—extreme, embodying hippiedom’s soppiest sentiments commixed with budding West Coast New Ageism. Yet given the company of Kienholz’s other, often comically brutal concept tableaux—from the wacky entombment of a grocery store, to the conveyance of a leather armchair supposedly made from flayed human skin—there is every reason to suppose its cloying wholesomeness was flavored with more than a soupçon of Kienholz irony. After all, this monument-cum-wall-caption was to be sold to a private collector, who would thus be able to buy, in three stages, The World, and all those who chose to manifest themselves in this “peaceful corner” of it.

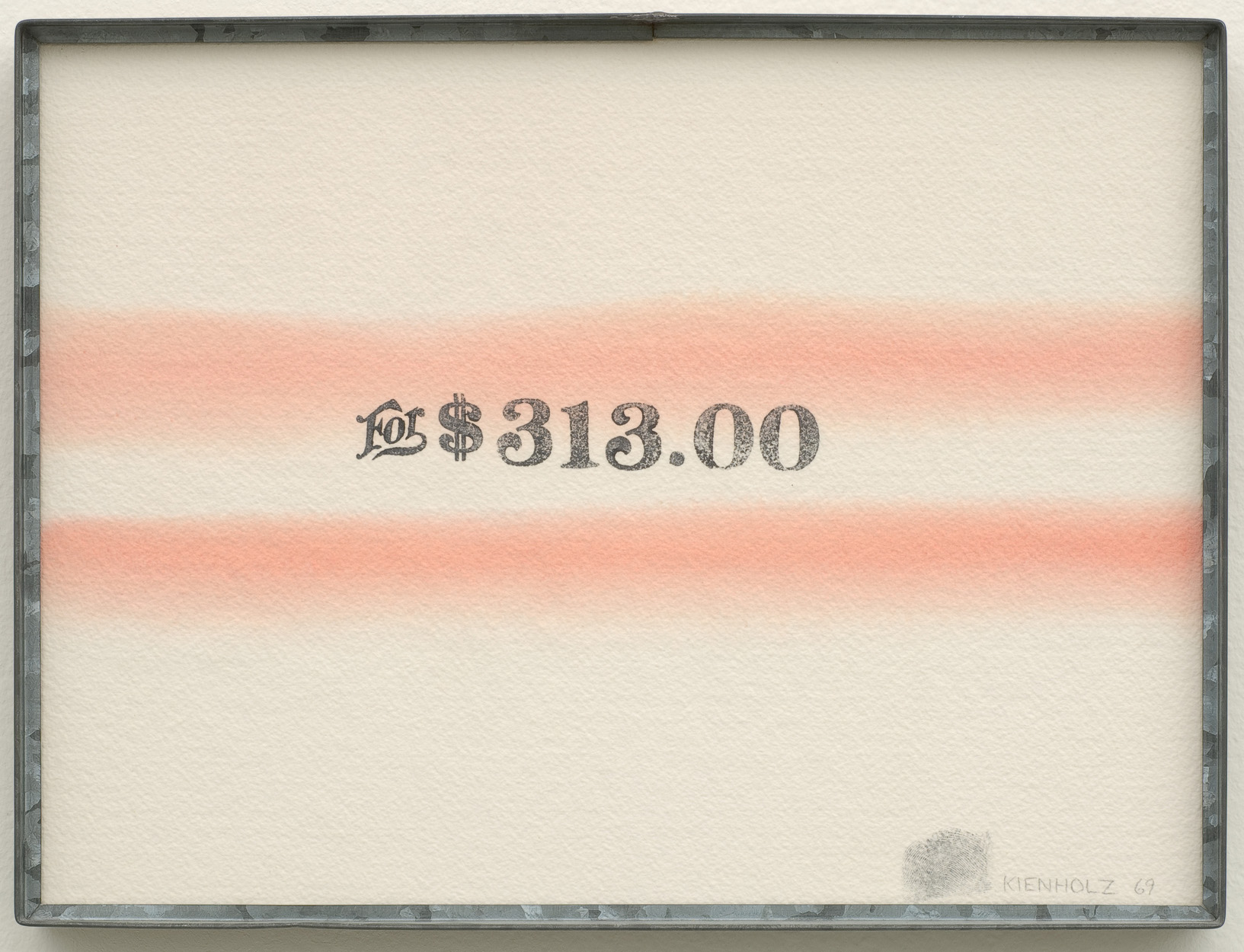

Indeed, Kienholz never lost sight of the status of the purchase when treating the immaterial. His pricing scheme makes the same distinction that Klein tried to cleave between physical and creative productivity—the former of which is considered the task of an artisan or mere preparatory work that clears the ground for the aesthetic creation (as when Klein repainted the whole interior of Galerie Iris Clert in preparation for the Void); the latter of which is, as Kienholz said of the Zones, “in its final distilled aspect … probably pure art,” and is to be paid accordingly, with substantial, arbitrary sums.16Indeed, in the late sixties, Kienholz would directly address the relationship between the purchase and the product with his Watercolors series, subtle watercolor washes on 12 x 16 in. rag paper, which he “bartered” for the sums or objects printed on them. Thus “nine screwdrivers”—the first in the series—was exchanged for nine of the items in question. Eventually Kienholz concluded that “some real cash was needed on the old barrelhead,” and he began stamping the center of the rag paper with monetary figures (“$43” as well as “$10,000”), which, of course, were sold for the amount specified, a concept that echoes Klein’s Epocha blu.17The more immaterial the art, the more concrete these sums, and the more the money seems to lose its fundamental character: no longer a pure means for exchange and accumulation, money becomes subject to the eccentric jurisdiction of the artist and the artwork.

Edward Kienholz, For $313.00, 1969. Aquarelle and ink on paper, 12 x 16 in. Copyright Kienholz, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, California.

To wit, both Klein and Kienholz created systems to control the exchange of their immaterial works. Klein specifies two possible ways of exchanging the Zones. The first is predicated on the event of an incomplete transfer, in which the collector has chosen to retain the receipt instead of burning it, and has thereby forsaken, according to Klein, any authentic value in the work itself. In this case, the collector is free to sell the receipt of sale—for double the asking price paid to Klein. The second manner of exchange, as Klein poetically notes at the bottom of the rules describing the ritual, is the transfer of one Zone to another person only on the condition of “absolute anonymity” for both parties.

Kienholz also restricts the conditions of exchange for his tableaux, demanding that all sales be registered with his lawyer, so that a concept tableau can never fully enter the art market unencumbered by the specific legal proceedings he has set in motion. This persnickety measure serves to highlight what is the case for both of these works: in their “final distilled aspect,” they seem to escape the typical sense of possession, and consequently the routine sense of exchange as it occurs within the art world. Like Klein’s Void, the cement store and the giant etiquette of The World are nonportable, nonexchangeable objects; even the leather armchair would repel the secondary market. To own these works is to own a very particular kind of property—one that cannot be developed or exploited, or transformed into something that can develop, exploit, and, perhaps most significantly, destroy something else. For that is what property in the West had come to in the most sinister and secretive cases, especially in the desert whose vastness and severity had so fascinated Klein. The West was not just the manufacturer of dreams; it was also home to the military industry, that manufacturer of nightmares.

In 1958, Klein wrote, “One must—and this is not an exaggeration—keep in mind that we are living in the atomic age, where everything material and physical could disappear from one day to another, to be replaced by nothing but the ultimate abstraction imaginable.”18In that same year, this assertion became a bit of tomfoolery in a letter Klein drafted to the president of the International Conference for the Detection of Nuclear Explosions, wherein he requested to be commissioned to paint all A- and H-bombs blue—Klein Blue, that is. “All I need,” writes Klein,

is the position and the number of A-bombs and H-bombs and a remuneration, to be discussed, that ought, in any case, to cover:

—The price of colorants.

—My own artistic contribution (I will be responsible for the coloring—in blue—of all future nuclear explosions).19