Richard Hawkins and the Haunted Dolls’ House

by Derek McCormack

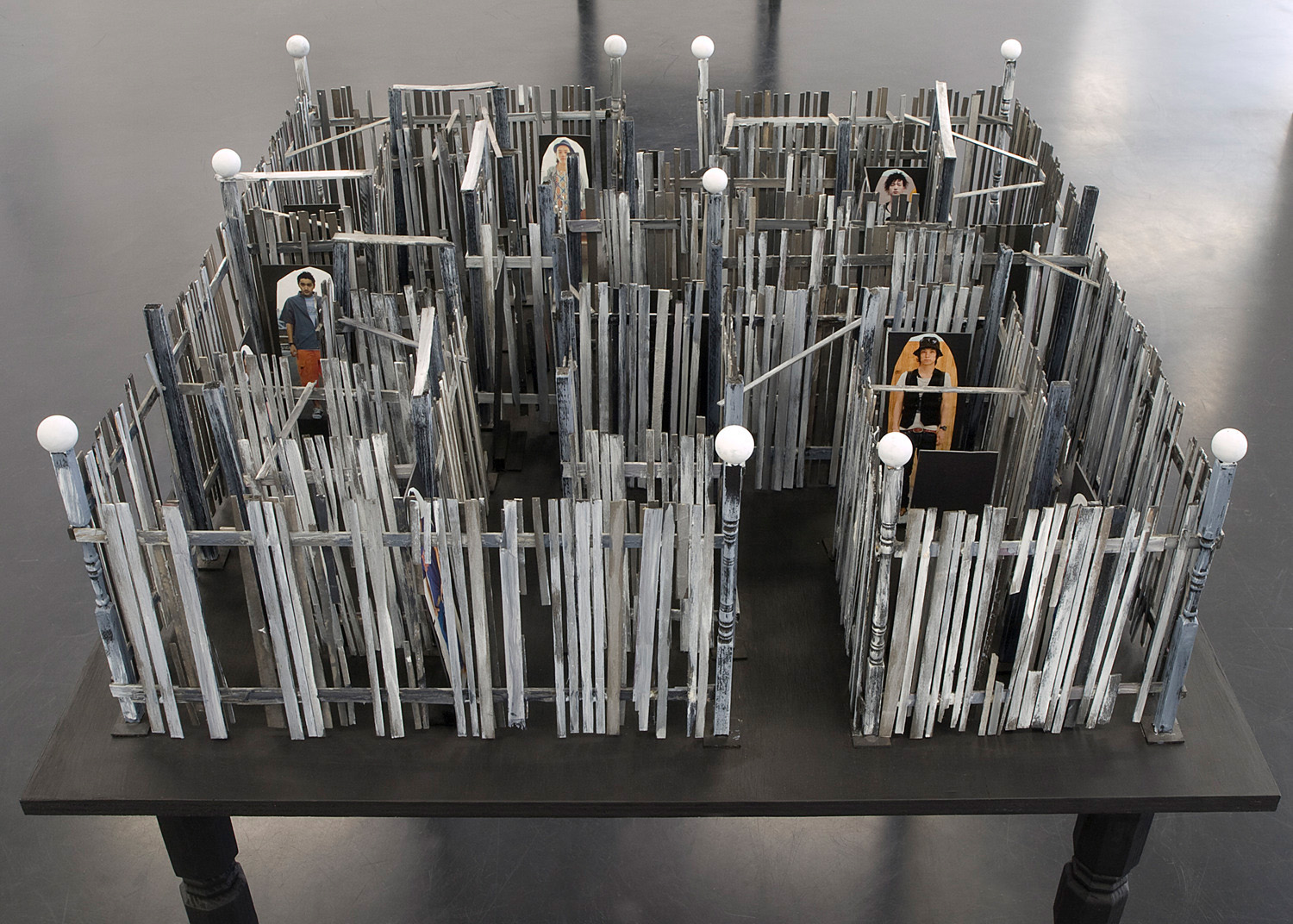

Richard Hawkins, Shinjuku Labyrinth, 2007. Wood, collage, and table, 40 x 37 x 37 in. All artwork images courtesy of Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles.

“THE HAUNTED DOLLS’ HOUSE”

A story by M. R. James

(Doctored by Derek McCormack)

“It’s a museum piece, that is,” Mr. Chittenden said.

“Well, I suppose there are museums that’ll take anything,” Mr. Dillet said as he pointed with his stick to an object which shall be described when the time comes. “I suppose you get stuff like this pretty often?”

When he said it, he lied in his throat, and knew it. Not once in twenty years—perhaps not once in a lifetime—could Mr. Chittenden, skilled as he was in ferreting out forgotten treasures, expect to handle such a specimen. The object was collectors’ palaver, and Mr. Chittenden recognized it as such.

“I’ve seen one, not as good as that, years back,” said Mr. Chittenden thoughtfully. “But that’s not likely to come into the market: and I’m told they ’ave some fine ones of the period over the water. No: I’m only telling you the truth, Mr. Dillet, when I was to say that if you was to place an unlimited order with me for the very best that could be got, I should lead you straight up to that one and say, ‘I can’t do no better for you than that, sir.’ ”

“Hear, hear!” said Mr. Dillet, applauding ironically with the end of his stick on the floor of the shop. “How much are you sticking the innocent American buyer for it, eh?”

Mr. Chittenden, now holding the cheque in his hand, saw Mr. Dillet off from the door with smiles, and returned, still smiling, into the parlour, where his wife was making the tea. He stopped at the door.

“It’s gone,” he said.

“Thank God for that!” said Mrs. Chittenden, putting down the teapot. “Mr. Dillet, was it? Well, I’d sooner it was him than another.”

“Oh, I don’t know; ’e ain’t a bad feller, my dear.”

“He’d be none the worse for a bit of a shake up.”

“Well, if that’s your opinion, it’s my opinion the gent’s put ’imself into the way of getting one.” Mr. Chittenden sat down to tea. “’E’s stuck with Richard ’Awkins now.”

“I’d ask you not to say that name out loud!”

“Yes, indeed,” Mr. Chittenden said, stirring. “Richard ’Awkins and ’is ’orrible, ’orrible ’ouse.”

And what of Mr. Dillet and his new acquisition? What it was, the title of this story will have told you. What it was like, you shall see for yourself.

“Wonderful, simply wonderful.” Such was Mr. Dillet’s murmured reflection as he knelt before it in a reverent ecstasy.

It was conveyed to Mr. Dillet’s spacious room on the first floor. It would have been difficult to find a more perfect specimen of a dolls’ house in high Victorian than that which now stood on Mr. Dillet’s large kneehole table, lighted up by the evening sun which came slanting through three tall slash windows.

It was quite six feet high, with casement windows that swung inward, and stained glass windows flanking the front door, and dormers that stuck out from the attic. A family of dolls inhabited it; a father, a mother, and a boy and a girl. A grandfather doll was tucked into a bed in the upstairs. Pages, of course, might be written on the furnishings of the mansion—how many frying pans, how many gilt chairs, what pictures, carpets, chandeliers, four-posters, table linen, glass, crockery and plates it possessed; but all this must be left to the imagination.

Mr. Dillet’s whim was to sleep surrounded by some of the gems of his collection. The big room in which we have seen him contained his bed; bath, wardrobe, and all the appliances of dressing were in a commodious room adjoining, but his four-poster, which itself was a valued treasure, stood in the large room where he sometimes wrote, and often sat, and even received visitors. Tonight he repaired to it in a highly complacent frame of mind.

There was no striking clock within earshot—none on the staircase, none in the stable, none in the distant church tower. Yet it is indubitable that Mr. Dillet was started out of a very pleasant slumber by a bell tolling one.

All over the dolls’ house, Mr. Dillet witnessed signs of a hideous commotion. He was so much startled that he did not merely lie breathless with wide-open eyes, but actually sat up in his bed.

As windows shattered, and plates shattered, and running figures passed within the windows, Mr. Dillet watched, wondering what to do.

Suddenly, as if caught in a wild wind, the front door to the dolls’ house flew open. A doll stepped forth.

A devil doll.

The hours of night passed on—never so slowly, Mr. Dillet thought. He had sunk down from sitting to lying in his bed. He closed his eyes but did not sleep as the demon doll continued to do what it had been doing; whatever it was, the racket was dreadful.

When sunlight slashed through the canopy of his four-poster bed, Mr. Dillet arose, and stared at what had been the centrepiece of his collection: for it was no longer the dolls’ house he had known.

“It’s destroyed!” Mr. Dillet said.

“It’s art!” said the devil doll as he straddled the chimney top.

Windows were without panes of glass, and the roof had been stripped of some shingles. Wrought-iron work had been wrecked—falling fences, collapsing cresting. Clapboard looked decrepit, dangling down, all dark tones of black and gray and blood red with wisps of white.

“What have you done? What have you done?” Mr. Dillet intoned over and over. The devil doll did not answer, nor did he have to; for he was Richard Hawkins, and he was perched atop the dolls’ house, and was holding the head of the son doll in his lap. It was cruelly clear what had occurred: he’d murdered the dolls, and fucked the dolls’ house in the ass.

“The Haunted Dolls’ House” was written by M. R. James. James, it’s said, was the father of the English ghost story; if his wasn’t the first ghost story about a haunted dollhouse, it was the first to be famous.1Its fame is enduring: though it was written in the 1920s, it’s still in print. It’s also in the public domain.

Richard Hawkins is an American artist who recently had a retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago; the retrospective opened at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles this month.

Hawkins works in myriad media. “Richard Hawkins: Third Mind,” the retrospective that opened in Chicago, included samples from many of them: paintings, collages, sculptures, found objects he’d altered.

Dollhouses—Hawkins works with them, too. “Third Mind” featured a pair of his haunted dollhouse sculptures, both from 2010: The Last House and Dilapidarian Tower. He made them the way he made earlier dollhouse pieces: he doctored store-bought dollhouses—rearranging and reassembling them, then redecorating them to look eerie and decrepit. They’re part art, part toys, part puzzles, part Halloween ornaments. They’re lit from inside; they’re part lamps.2

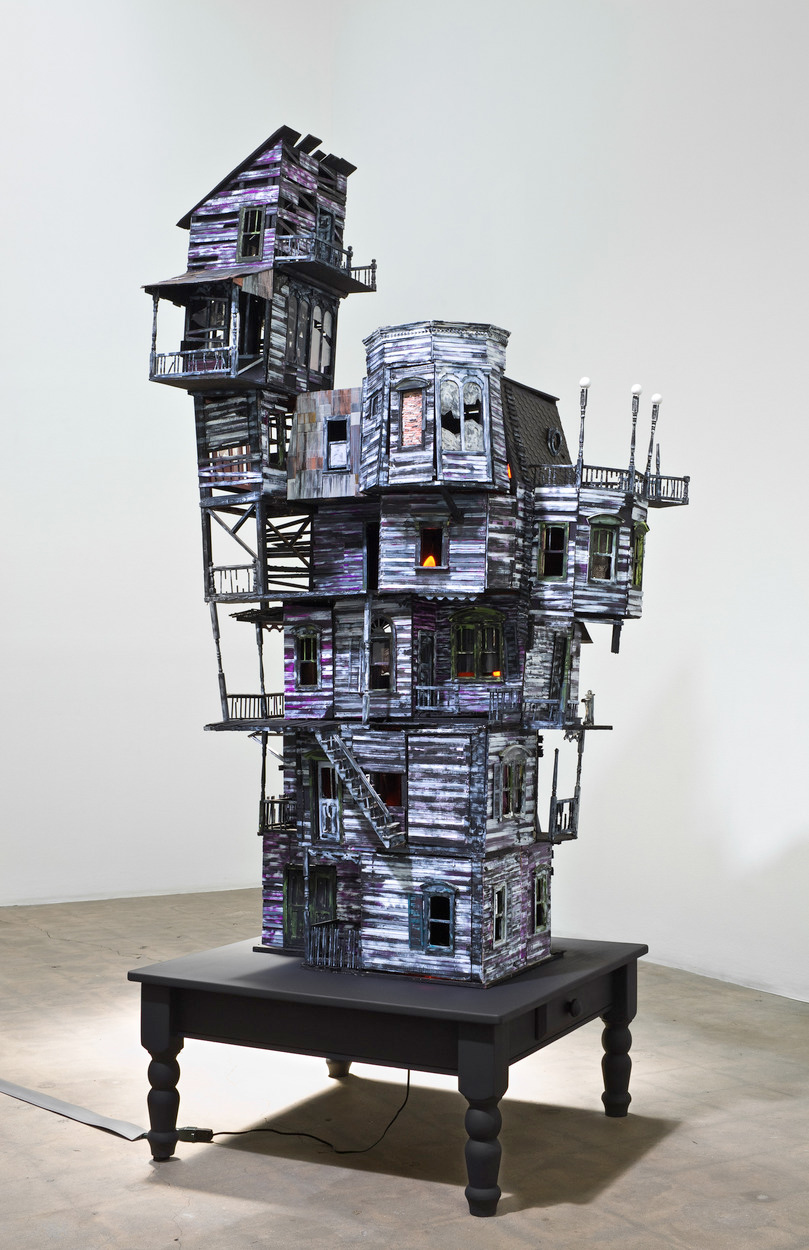

Richard Hawkins, The Last House, 2010. Altered dollhouse, lighting, and table, 89 x 36 x 36 in.

The Last House is a ramshackle Victorian made up of multiple ramshackle Victorians. It rises up and out, growing larger as it goes: a metastasizing mansion, a haunted house turning into a haunted slum. Dilapidarian Tower is eight stories tall, a doll tower constructed from dollhouse salvage. It’s streamlined, or it could be if there weren’t a porch tacked on here, a balcony there. On a couple of porches, laundry hangs from laundry lines. Ghosts do laundry? Ghosts wear clothes? Q: What did the ghost in the Rick Owens store say? A: I’d be caught dead in that.3

If there’s a Jamesian history of haunted dollhouses, there’s a hidden history, too: a Hawkinsian history in which dollhouses are haunted not by dolls, but by ideas.

In “The Haunted Dolls’ House,” James established a blueprint for haunted dollhouses. The dollhouse shows no signs of being haunted. The façade is flawless; the furnishings—chairs, beds, buffets and tables—are faithful reproductions of those found in historic homes. In the decades that followed, it came to be a cliché of haunted dollhouse stories, from The Dollhouse Mystery by Carolyn Keene to The Dollhouse Murders by Betty Ren Wright: exemplary exteriors and immaculate interiors disturbed by spooky doings.

In “The Haunted Dolls’ House,” it’s not the house that’s haunted; it’s the dolls that dwell in it. The Mom and Dad dolls murder the Grandfather doll for money; later, a demon that looks like a frog with a fringe of gray hair on his head murders Mom and Dad’s son and daughter. Since James’s story, it’s been the same—the same in Hell by Kathryn Davis as in The Haunted Mansion Mystery, a Barbie book: in an ornate dollhouse appointed with period accoutrements, dolls act out the mad, murderous passions that humans attempt to tamp down.

In 1945, the writer Flora Gill Jacobs came across a dollhouse in the barn of a New Jersey antique dealer. “It was cobwebbed and dirty,” she later wrote in A World of Doll Houses, “with a number of broken windows. Until it was repaired, it was always thought of as ‘the haunted house.’ ”

What makes a dollhouse haunted? For Flora Gill Jacobs, it was dereliction and disrepair. Spooks? Spectres? Superfluous. To Jacobs, the soul of a haunted dollhouse was not devilry, but decor.

It was the first dollhouse she ever bought. Then she bought another. And another. She became a dollhouse collector and scholar: A World of Doll Houses, which was published in 1953, was the first survey of the subject. She later wrote The Doll House Mystery, a Jamesian tale that unfolds in her New Jersey dollhouse. She went on to found the Washington Dolls’ House and Toy Museum, the first museum of its kind in the United States. There she showcased her “haunted house,” which was no longer haunted: she’d polished it up and appointed it with the proper Victoriana. It’s too bad that Jacobs repaired her New Jersey house: in its dirty condition, it represented a break from the Jamesian dollhouse and a harbinger of Richard Hawkins’s works.

Hawkins’s dollhouses haven’t been disturbed, nor are they about to be disturbed; they are disturbed. Hawkins seems to be saying: Shouldn’t a haunted dollhouse look haunted? There are no dolls in Richard Hawkins’s dollhouses; there are no dolls to sin or be sinned against. Hawkins is asking: Must a dollhouse be haunted by dolls? Must a dollhouse be haunted by something—anything—or might it simply be haunted by hauntedness?

A dollhouse on a table on a stage.

A magician opens it up: it’s empty.

After closing it, he says abracadabra and—voilà!—conjures a doll: actually an assistant, a woman, always a woman. The dollhouse flies open, the roof flies off and she’s atop the table, dollhouse around her feet.

How did he do that? The secret’s simple: a false back in the dollhouse, a false top in the table, and an assistant able to contort herself until it’s time to stand up.

The Doll’s House illusion was created by the English comedian and magician Fred Culpitt, and dates to 1927, a mere two years after M. R. James published “The Haunted Dolls’ House.”4By World War II, the illusion was being copied by acts in every country. Suppliers sold plans for a slight variation: an Oriental Doll’s House illusion. Magic!, an exhibition of magic history at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in 2009, showcased such a house: a standard Doll’s House illusion painted like a pagoda, with winged eaves slapped onto the structure.

Richard Hawkins, Stairwell Down, 2007. Altered dollhouse and table, 42 x 36 x 36 in.

“Madhouse of Mystery”—Bill Neff, an American magician, toured a show with this name in the years after World War II. It was a spook show. It played movie palaces. Before a monster movie screened, Neff would run through a series of sinister-seeming illusions—the Spirit Cabinet, the Cremation illusion, the Frame of Life and Death illusion—against a frightening backdrop: a forest full of buzzards and bats. The Doll’s House Illusion was part of his presentation. He called it the Haunted House on Drury Lane, as if Englishness accentuated the eeriness. He gave it a fearful facade: his house was black, with glow-in-the-dark door and window frames. A doll didn’t rise from it; a ghost did, a woman in a white sheet and hood. The show ended with a blackout: the theater lights died, and spooks and skeletons suspended from strings swept out over the crowd. Then the movie started.5

The Doll’s House Illusion belongs to both the Jamesian and the Hawkinsian traditions: it bridges them. As in James’s story, the dollhouse in Culpitt’s illusion was a locus for magic. In the story, the magic is supernatural; in the illusion, it’s a trick tricked out to seem supernatural.

A haunted dollhouse that looks haunted—the dollhouse that Bill Neff designed for his “Madhouse of Mystery” presaged Hawkins’s sculptures by decades. Then again, so did the pagoda dollhouses. Hawkins’s sculptures aren’t only haunted by the idea of hauntedness, but also by orientalism.

Bordello on rue St. Lazare (2007) is an early dilapidated dollhouse. It depicts the boy brothel where Proust liked to play. On the wall: a portrait of Proust. The building’s abandoned: no dolls. It’s boarded up, but badly—furnishings have been left behind: an Oriental rug, some Japanese vases, a Chinese palace lantern with red tassels.

Stairwell Down, another dollhouse from 2007, is a dead ringer for the Bordello, save that it’s not decorated in an orientalist style. Instead of sitting on a tabletop, Stairwell Down is stuck to the table’s underside, hanging upside-down like a stalactite, or snot. It seems to point straight down to China, or Istanbul, or Siam, or Shangri-la, and to the boys who sell themselves there.

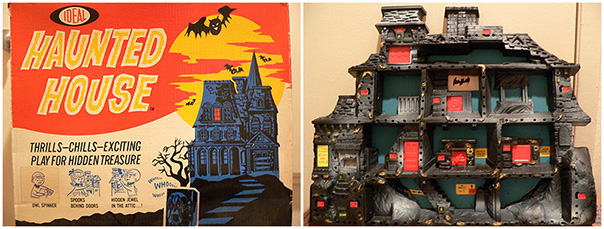

Haunted House by Ideal is a board game from 1962. It’s black; the box is decorated with bats. It’s a dollhouse of sorts: a very shallow Victorian with visible rooms. In its day, it was the only board game that stood upright on a tabletop. Players spin an owl spinner and proceed through the rooms. In each room, a locked door. Stick a plastic key into a door and a message pops out: “Go back to Room B.” Stick a key into another door: “Go to the start.” Another key, another door: a ghost pops out. There’s a prize concealed in the attic: a plastic ruby.

Haunted House boardgame box and house by Ideal, first produced in 1962.

The Hootin’ Hollow Haunted House by Marx was released at around the same time as Ideal’s Haunted House. It’s made of metal—tin that’s been lithographed with broken windows and broken clapboard. What appear to be typewriter keys protrude from the side of it. Press a key: a ghost swoops across a window. Press a key: a vampire pops out of the chimney top.

Dollhouses are for girls. When a boy wants a dollhouse, he’s faggy. When faggy boys grow up, they become fags. In the 1960s, toy companies began selling dollhouses for boys. They weren’t called dollhouses: they were games, or play sets. They didn’t look like Barbie’s Dream House: they were macabre, the more macabre the better. Dream Houses? Dread Houses. Built not for Barbie, but for Barbey d’Aurevilly. Boys were allowed to want them. The Haunted House game was cool. Mad Monster Castle by Mego was cool: Mad Monster action figures played there. Action figures sold separately. The castle was cardboard—pink cardboard.

The Weebles had a Haunted House. It wasn’t so cool.6

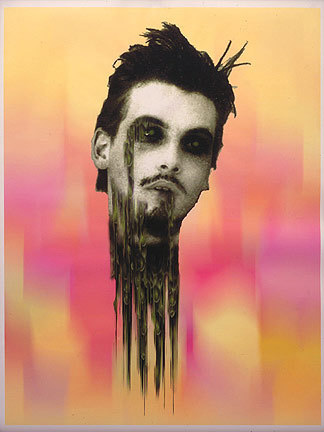

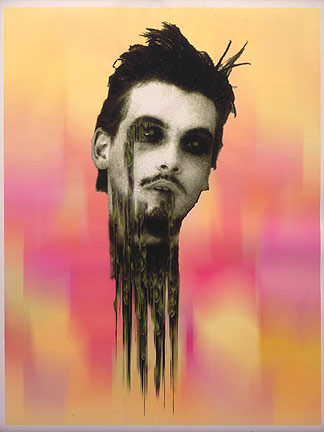

A lot of the art in “Third Mind” has a toylike taste. Disembodied zombie skeet pink (1997) is a print of Skeet Ulrich—his detached bleeding head, anyway—floating on a pink field. It’s from a series: there are disembodied Bens and Johns and Georges, too. The zombie boys bring to

Richard Hawkins, Disembodied Zombie Skeet Pink, 1997. Inkjet print on paper, 47 x 36 in.

mind the dates in Mystery Date, a board game from 1965. In that game, girls tried to get a good date: the bowling date, or the skiing date, or the formal dance date; in Hawkins’s hand, ghouls come calling, and they’re cute. Black tassels of blood drip off them.

Shinjuku Labyrinth (2007) has a board game feel to it, too. It’s a maze made of scale-model wood fence slats. In the maze’s dead ends are collaged characters, cute male pop stars and movie idols clipped from the pages of Japanese magazines. Arrayed on a black tabletop and assembled from artfully worn and falling-down wood, the labyrinth’s a scary affair: the boys cruising within it are uprights, like the spook pieces in Disney’s Haunted Mansion board game. It radiates desperation and dark desire. It’s an ideal toy for Hawkins: Fisher Price by Vincent Price.

But what does it mean when grown men have haunted dollhouses? “The Haunted Dolls’ House” was haunted by faggotry in the form of Mr. Dillet, an adult—without wife or children—who lived among the gems of his dollhouse collection. And what about the frog-faced ghoul with gray hair? Don’t gays love to murder children?

With dollhouses as with lovers, some open in the front, and some open in the rear. Which way do Richard Hawkins’s haunted dollhouses open? Maybe they don’t open; maybe they open in ways no dollhouse has ever done before. They’re gay and more: transvestite, transgendered, between and beyond genders. Decadent desire haunts them; in turn, they expose and exaggerate desire and its seemingly supernatural powers.