The Journey West

by Thomas Lawson

Shirley Irons, Amy’s Sky, 1998. Cibachrome, 22 x 32 in. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles.

The launch of East of Borneo marks the convergence of two very distinct lines of thought. What is the nature, and the future, of art magazines? And how might we give form to the sprawling history of art in Los Angeles, a form that can be generative and productive, not merely descriptive or fancifully speculative? In retrospect I realize I have been mulling over these questions for decades, since first getting into the art magazine business with REALLIFE Magazine, in 1978, and since first visiting Los Angeles, in 1980. However it was not until the emergence of the so-called Web 2.0, and the ability to create interactive social networks, that I began to sense there might be an answer to both questions in the same place.

In the summer of 1980, escaping the oppressive humidity of New York City, Susan Morgan and I came out to Los Angeles for a couple of weeks. We stayed with a friend who was renting a bungalow in the Valley, a house with a pool in the backyard! We borrowed an early ’60s Rambler from another friend – it had been stored and unregistered for several years, but was in reliable running condition, although the back doors were tied together with some old clothesline. In this rounded, gray machine that looked so like the IBM typewriter we used to put together the final copy of each issue of REALLIFE Magazine, we set out to discover Los Angeles.

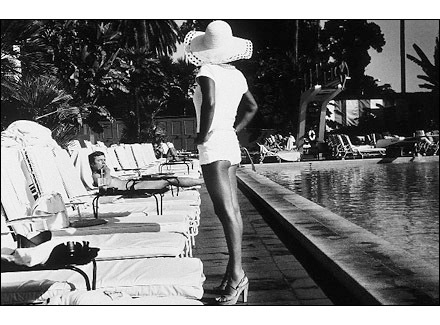

Anthony Friedkin, Woman by the Pool, 1975. Silver gelatin print, 16 x 20 in. Coutesy Stephen Cohen Gallery, Los Angeles.

Because we were publishing a magazine, we made it a research trip, meeting and talking to quite a range of people. We experienced an expansive feeling of discovery as we drove the freeway, gaining a sense of place much broader, but also less specific than we knew in Lower Manhattan. There, most of our daily business was conducted on foot, meeting and talking to people face-to-face, often in unplanned encounters. In many ways we lived as villagers, members of a shadow community of artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers who walked the same streets, frequented the same bars and restaurants, dropped in on the same galleries, performance spaces and movie theaters. It was normal to wake up with an idea for a project, run into two or three people during the course of the day, see that idea develop, and by evening have a plan evolving. In that chance-driven spirit, we had collected names and phone numbers of people in Los Angeles that people in New York thought we should meet. As we drove from appointment to appointment across the Los Angeles basin we quickly realized that it was not the route traveled on any given day that provided interest and material, but the variety of destination. With each stop unanticipated resonances enlivened our experience, while anticipated epiphanies often failed us.

We visited one artist in his studio high up above the ocean in Topanga. The building had a wall that lifted up, opening his entire workspace to the burnished gold of the canyon beyond. We didn’t know any artists who lived that spectacularly well, and we couldn’t figure out where the work came from. Another day we went to the house and studio that R. M. Schindler had built for himself, at that point nearly collapsed on itself, a gem of creative optimism lost in an oppressively conformist area of bland and pointless apartment buildings. Here, we realized, was the prototype for the glamorous studio in the canyon, with its combination of inside and outside living and working, sited (as Schindler’s place had been originally) on the edge of the city, an intensely private space that existed to shun the everyday rather than engage it. Later, visiting a painter in a storefront studio on Washington Boulevard, we recognized a situation that was more urban, familiarly dissatisfied and anxious.

The following week we went down to the Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, another near-ruin in a residential neighborhood that seemed to pay it no heed. The towers were spectacular in their vertiginous rise above the obsessively tiled surfaces and cozy seating nooks we could glimpse over the wall, but again we felt we were looking at something out of time, beyond history as we had come to understand it. Hoping to take in a more expansive view, and better understand the lay of the land, we drove up to the Griffith Observatory, our clothesline-tied backdoors swinging wildly with every curve up the steep climb. The summer haze meant we saw little more than the wildness of the park, the scrub brush and dusty trails, and up on the parking plaza, the tour bus crowds pushing to get their pictures taken.

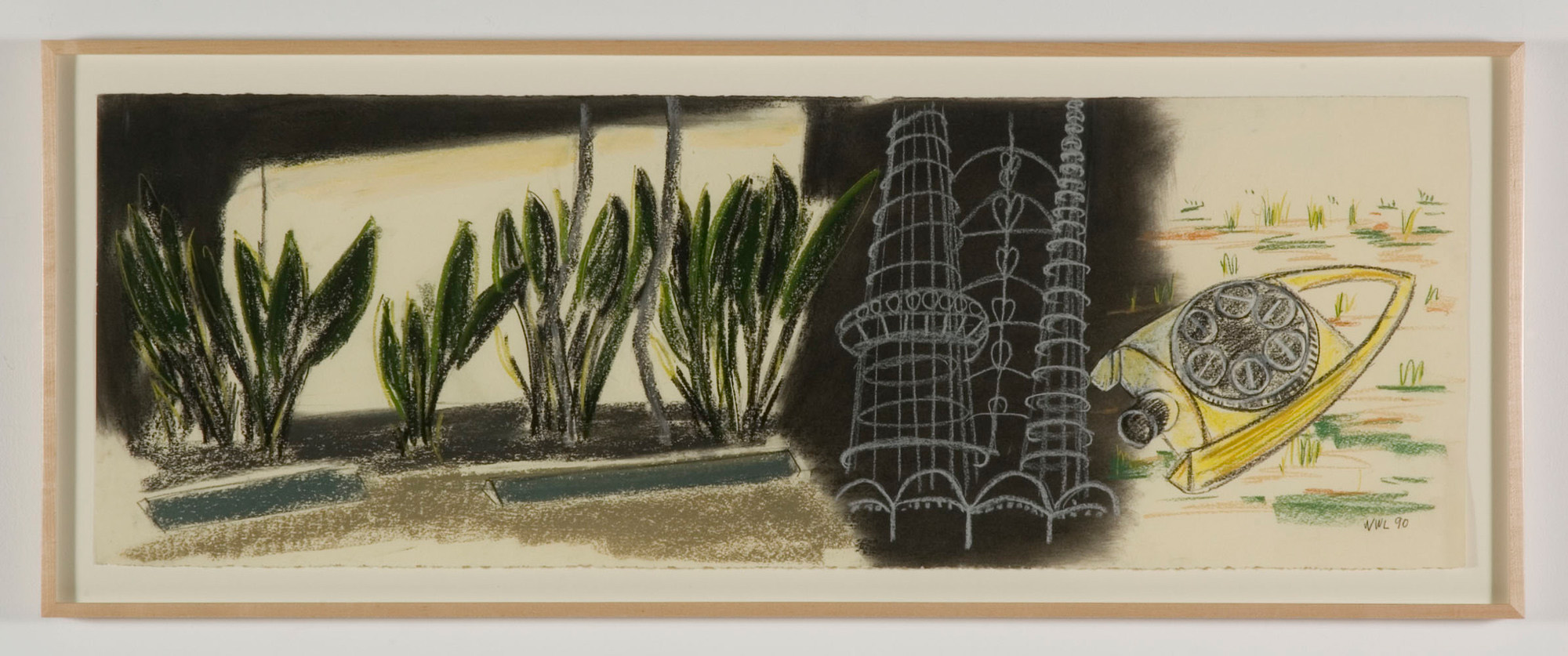

William Leavitt, Rodia Tower with Lawn Sprinkler, 1990. Pastel on paper, 15 x 43 in. Courtesy Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles.

Coming from New York we found all this both exhilarating and baffling; Los Angeles seemed to be a city hiding in plain sight. There was plenty to see, interesting people to talk to, all easily accessible by the sporadically flowing freeway. But that veneer of easy connectivity masked a deeper, and more troubling, sense that nothing was easily available, a misleading perception of nothing going on. This was a city of outposts and easily missed landmarks connected by a sprawling, historical disposition not to connect; a deeply unsociable city – not unfriendly, just unsociable, the opposite of places like New York or Paris with their gabby rush to embrace and discard. When we left Los Angeles we had some ideas for future articles, but we didn’t have a satisfying grasp on the place.

REALLIFE Magazine was very much the project of a walk-around city. We had an editorial point of view, which was that we wanted to provide a forum for younger artists who saw themselves operating in a post-conceptual landscape, with an interest in connecting to issues of everyday life. That is to say we were still working in the shadow of a well-known history, a narrative of progress and upset that we tended to accept as more or less given. The wrinkle in that acceptance was an ever-present conviction that the somatic experiments of Surrealism held out a lot more promise than our more academic peers allowed. Our editorial process had a trajectory, but it was one easily, and willingly, sent off track by an interesting chance encounter. We sought openness within a structure framed by opinion, and sought that through the old-fashioned networking of the street. Los Angeles proved fatal to this method, and the magazine came to an end shortly after the two of us moved here in the early ’90s.

In 2002, after a ten-year break from the business side of art magazines, I joined the editorial team of Afterall, a self-described “journal of art, context and enquiry” that had begun as a counterweight to the market-driven art talk prevalent in London in the ’90s, and that maintained a purposefully old-school attitude to the idea of the art journal as something deliberately out of time. The founders, an artist and a curator, designed an editorial process that took the form of a twice-yearly seminar to discover the most interesting artists to discuss. When they invited me to join them, the idea was to expand this method; investigating international art from two separate but simultaneous perspectives, that of London and Los Angeles. For several years this proved to be a rich, intense, and very productive experiment. And then an intellectual exhaustion set in and the project drifted into an ill-defined state of ennui. Paradoxically the root of this exhaustion was our lack of rootedness; in a fundamental way the journal had no point of view, only a premise. Unmoored in the jet stream, our two bases separated, buffeted by argument without end.

In the 21st century the ramifications of this rootlessness and the practical challenges facing publishing began to require ever more radical responses. The small bookstores that had once supported small magazines were closing at an increasing rate. Museums were turning their bookstores into gift shops. Fluctuations in the currency markets made it increasingly difficult to budget production costs in an international context, and then the huge economic crash made everything impossible. But the biggest challenge of all was the Internet, which manages to make everything simultaneously local and international. When Susan and I were publishing REALLIFE Magazine we had a substantial subscriber base, a much larger figure across the United States than Afterall ever achieved, despite significant institutional backing. But of course before the Internet, people had to subscribe to little magazines if they wanted to keep up-to-date, whereas now we inhabit the complex world of websites, blogs, aggregators and Twitter feeds, and can keep informed by the instant.

What this all suggested to me was that what an art publication could be now was something both more participatory and more traditionally edited. I still believe that people may actually like some editorial guidance – the most successful blogs seem to be the most opinionated. But these blogs tend to a linear, one-thing-after-the-other format that runs counter to the open horizontality of communication offered up by the hyperlink. Discussions flare, and can become engrossing, but they tend to be one-dimensional, focused on one issue at a time. I found I was hungering for a more complex participation. As a writer I have become accustomed to working in a way that allows skipping back and forth as a text builds, checking references, finding new evidence as a result of lateral moves across the Internet. A few online publications allow readers a similarly multifaceted experience, although most quarantine reader participation in the shadow zone reserved for comments. Until now no art publication has offered this kind of experience.

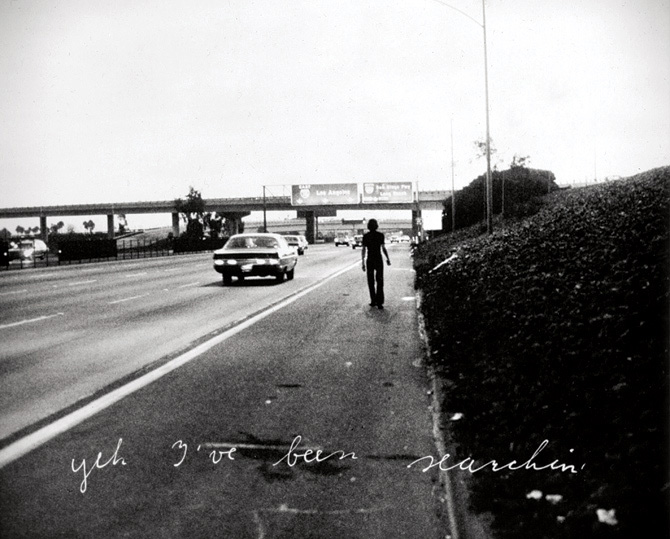

Bas Jan Ader, In Search of the Miraculous (One Night in Los Angeles), 1973. Copyright Bas Jan Ader Estate, courtesy Patrick Painter, Santa Monica.

As you navigate the site today you will discover that East of Borneo incorporates the benefits of online media not only for timely art-related content, but also for lively dialogues and the sharing and distribution of research and archival material. Our articles incorporate and offer the materials—video, audio, links and texts—that the author drew from. Users can upload their own relevant contributions, creating a growing archive of associated content. Topics will develop depth over time as material accrues, becoming substantial repositories of information and interpretation.

What we imagined was an intricately interwoven site that would allow us to build an archive of Los Angeles, past and present, using the power of a networked collectivity to create depth and complexity. To some Web 2.0 is old news, but established magazines are only slowly awakening to its challenges and possibilities. East of Borneo’s genesis has been long and deliberative: several years of thinking past the delights and constraints of the printed page, and one very intense year of thinking through the actual possibilities of current online publication.

I am tremendously proud and excited about all this, and hope you will share my enthusiasm. Visit us often to watch the site grow in both content and interactivity as we roll out further features. Visit us often to upload that telling image, indispensible text, incredible link. Join us on this journey.