The Mohn Games

by Carol Cheh

Meg Cranston, Made in L.A. 2012 installation view at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo by Brian Forrest.

In March of this year, the Hammer Museum introduced the Mohn Award—a $100,000 art prize offered in conjunction with their new “Made in LA” biennial—to some fanfare. Blending elements of the Whitney Biennial’s Bucksbaum Award and Britain’s controversial Turner Prize, the Mohn Award will recognize a single biennial artist, selected from among 60 participants, with a hefty cash sum and the publication of a monographic book on the artist’s work. A jury of four professional curators chose five finalists shortly after the exhibition opened on June 2 and now, in a unique and attention-grabbing twist on the classic art prize format, the winner will be selected by public vote.

The Mohn Award is the latest in a series of flag-planting, publicity-generating spectacles that have altered the fabric of LA’s art landscape. If the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time” initiative offered corrective histories, and Michael Govan’s upgrading of the LACMA campus with monumental, crowd-pleasing installations by Chris Burden and Michael Heizer provided iconic visual references, the Mohn Award could be said to add some serious bling to the mix. Money talks and, as many have noted, this award puts Los Angeles and the Hammer Museum on par with the biggest global players in the art prize market.

The award seems to have met with approval in the international arts community, as seen in a proliferation of brief news items announcing its arrival. Here on the ground in LA however, artists, curators, and other close observers of the scene received news of the award with an interesting mix of guarded approval, trepidation, unease, consternation and outright criticism. On the day that the five finalists were announced to the public, for example, I was at Ooga Booga bookstore for the launch of an artist’s book and found myself chatting with one of the biennial artists who was not a finalist for the award. “Yeah, I was hanging out with a bunch of the other artists last week, and we were all talking about how weird this whole thing is,” he confided to me. “No one wants to be the asshole who wins.” A few minutes later, one of the finalists walked through the door and was instantly greeted with chatter and excitement about the nomination. Looking sheepish, she smiled and found a way to quickly excuse herself from the room.

After speaking with a range of people in the community, a number of common concerns came to the fore: that the award continues a depressing museum trend toward media-oriented spectacle; that it dominates the public discussion about the biennial exhibition at the expense of more considered discourse about the work; that it’s booster-ish and promotes a winner-take-all mentality; and that the uneven distribution of resources instigates a sense of competition among the artists, one out of place in a community that more often prides itself on collaborative spirit and mutual support. While some were careful to say that they ultimately thought the award would be a fine and good thing for LA art, some outright dismissed it for these and other reasons.

The fears that have been expressed are not necessarily unfounded. Jarl Mohn, the philanthropist, venture capitalist, and marketing specialist behind the award, has said that he was inspired by the Turner Prize, which is considered the most successful and important of art awards. If we look at the history of that award, we see for the most part a rather brutal public relations campaign designed to awaken a hitherto sleepy and nostalgic British populace to current developments in the visual arts.1It was a campaign that, as the uproar surrounding Damien Hirst’s cow and Tracey Emin’s bed will attest, thrived on controversy and simplistic, sensationalistic coverage of the art on display. The Turner Prize certainly did what it set out to do, helping to put the Young British Artists at the forefront of art world consciousness and to ensure that the Tate Modern was built. However, this success came at a considerable cost.

Many Turner finalists and awardees have spoken over the years of how traumatizing the award process is, as it subjects the artists to a firestorm of invasive and often negative media attention, not to mention the public humiliation should they lose. Mona Hatoum, a finalist in 1995, called it “hell,” noting that “the work gets classified in an artificial, almost irrelevant category and compared with that of other candidates, with which it has nothing in common.” Karla Black, a 2011 nominee, remarked, “It’s not sport. There’s no such thing as ‘best.’ It’s a bad way to think about art.” Other artists have notably turned down their nominations. In 1997, Julian Opie declined because he “would have found putting [his] work into the uncontrollable conditions of game-playing stressful.” Lucy McKenzie took a pass in 2007 because she was unwilling to “compromise the flexible and critical dialogue” around her work.2

While I don’t believe that things will ever reach such a fever pitch around the Mohn Award, given the fact that we lack a tabloid market for the visual arts here, I do find it striking how the above artists’ comments echo many of the comments made in Los Angeles. What some fear will happen has already happened many times over since the Turner Prize was launched in 1984. So on the eve of the announcement of the first-ever Mohn Award winner, it may be useful to take a closer look at some of the issues that this award has raised in our community. In my mind, these boil down to two essential concerns: artistic agency and the importance of community.

“How Can I Maintain My Agency?”

During a recent studio visit, Zoe Crosher and I were talking about an unrelated issue when she made the following observation: “Back in the sixties, there was a clear division between establishment and non-establishment, between selling out and not selling out. Things are no longer so black and white. The question has now become, how do I work and still have agency as an artist?”

Crosher is far from alone in this observation, as I’ve heard many artists talking about “agency” in relation to the career paths that they are forging for themselves. It is this same concern with agency that I hear in the complaints of the British artists quoted above; indeed, it seems that a serious loss of agency did happen to artists who saw their work framed inappropriately, or who, like Tracey Emin and Mark Wallinger, found themselves unable to work for months following their Turner Prize experience.3In their criticisms and questions around the Mohn Award, LA artists seem most of all to be struggling with this issue of how to retain their own agency.

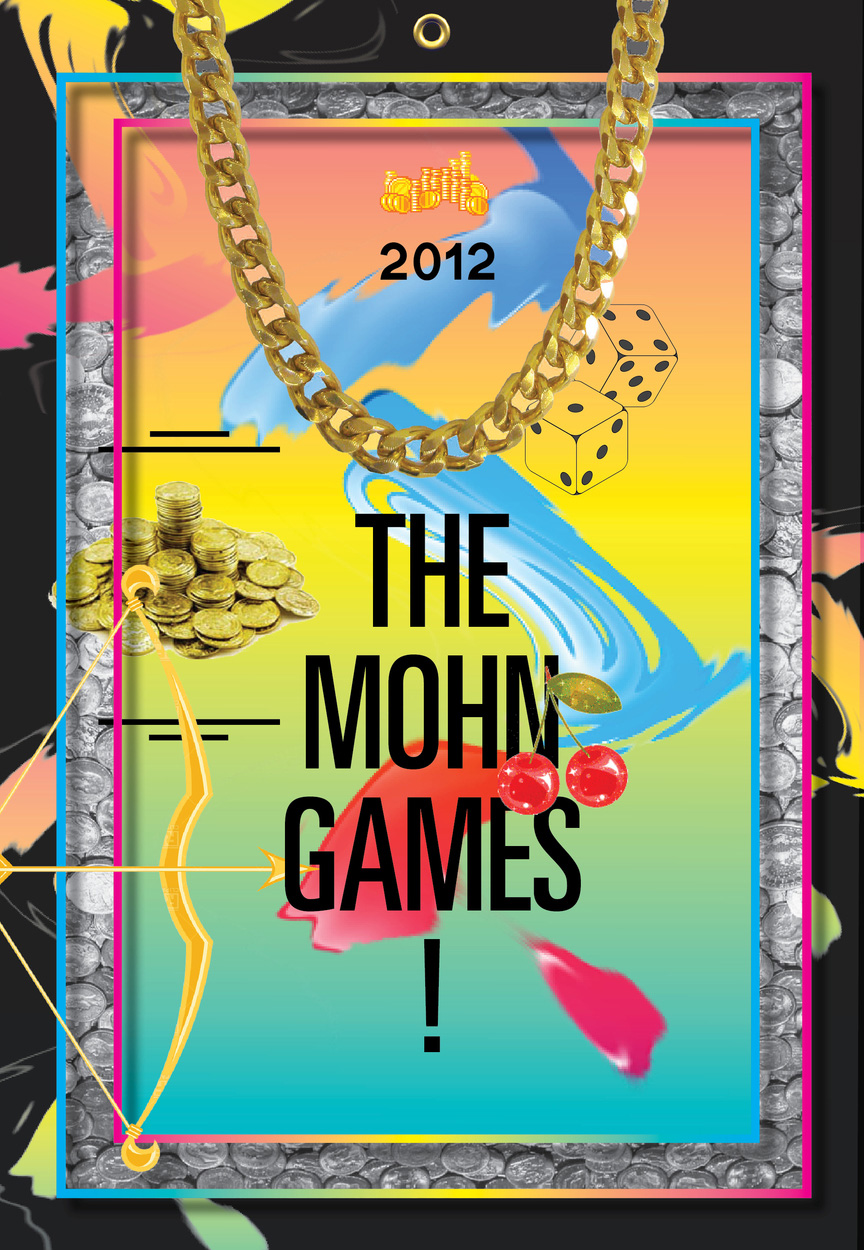

Tanya Rubbak, The Mohn Games, 2012.

Earlier this year, before the five finalists were announced, I was among a small group of artists, writers, and curators who gathered for dinner following a performance art event at LACE. Talk of the Mohn Award came up and we began discussing the odds of who might win. Did the artists exhibiting at the Hammer have a better chance than the artists exhibiting in the two satellite venues [LAXART and the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Park]? Would the jury favor emerging or more established artists? Could the artists in fact be handicapped according to their exhibition histories, press coverage, and social/professional networks?

Eric Kim, co-director of the local performance art space Human Resources, proposed that we start a betting pool, and we decided to move forward with this as a serious project. We met the following week to iron out logistical details and soon went live with a Facebook announcement and a WePay account to accept payments before the finalists were announced on June 27. The Mohn Games (a nod to “The Hunger Games”) got an incredible response online, with many in the LA art community participating and appreciating it as a smart and critical way to apprehend the award, one that brought the spectacle back into the grasp of artists and their friends.

Fiona Connor, Lobbies on Wilshire, 2012. Installation view at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo by Marianne Williams.

Simply picking up this catalogue was a great opportunity to interact with the artist and her work; but to read it was to be greeted by a wonderfully freeform explosion of voices discussing art, the Hammer, the work in the show, larger social issues, and their personal lives. In a museum environment, where only sanctioned voices and perfected presentations are given play, this catalogue—with its multitude of typos, uncited quotations, casually shared opinions, improvised layouts, and exposed production process—was an invigorating breath of fresh air.

When I told Connor that I was working on an essay about the Mohn Award, she immediately directed me to a 59-page transcript of an artists’ gathering at Barnsdall Park that she had attended the week before. It soon became apparent that this was the same gathering that had been referred to by the artist I was chatting with at Ooga Booga, and it was initiated by biennial artist Ashley Hunt. Hunt was interested in creating a space—artist-generated and separate from the “official” discursive spaces of the biennial—for the 60 participants to have some meaningful conversation with one another on how they felt about the exhibition and their positions within it.

Inevitably, much of the first meeting, which occurred a few days before the five finalists were announced, was devoted to discussing the Mohn Award. Grievances get aired at length, and recurring throughout the transcript is a complaint that the Mohn Award—like the Getty’s much maligned “Pacific Standard Time” poster campaign that celebrated only heavy hitters like Baldessari and Ruscha—had been unleashed upon these artists without their permission or input, introducing a dynamic of competitive spectacle that was uncomfortable.5The timing of the prize’s announcement had also been awkward, having been “sprung” upon them at a celebratory dinner after their work had already been installed. They bemoan the loss of the artist’s voice and discuss ways to retrieve it, such as refusing the prize if it is given to them, or by distributing it among the other 59 artists. They also talk about how the prize reduces the quality of the dialogue around the exhibition—but the more they talk, the more they find themselves counteracting the prize’s effects. They make plans to keep meeting every week.

A few weeks later, I’m at Barnsdall Park and I run into this same group of artists, now engaged in a talk with biennial artist [and Mohn Award finalist] Simone Forti about her exhibited work. One of the things that had come out of their weekly meetings was a desire to keep forging relationships with one another through mutual studio visits, and here they were doing just that. Connor later told me that she felt the group had realized that this was what they wanted all along and that, for the most part, they had processed their feelings about the Mohn Award and were over it. They had moved on.

“Community Is More Important”

In conducting research for this essay, it became apparent to me how deeply important a sense of community is to the LA art world. Perhaps LA’s geography naturally encourages so much isolation and loneliness that community must constantly be sought, lest one becomes permanently lost. Perhaps the city’s long history as a haven for utopian thinkers encourages it. But for whatever reason, collaboration, mutual support, and shared resources are what fuel the engine of art production in LA. In such an interconnected ecosystem, giving a large cash prize to a single recipient can seem a bit discordant.6

When speaking on the record about the possibility of winning the prize, the Mohn Award finalists tended to deflect attention away from themselves. Asked on KPCC Radio’s Off Ramp what she would do with the $100,000 if she were to win, Liz Glynn’s answer was “I would get space for other artists to do something awesome.” In my interview with her, Forti said that she couldn’t keep all the money for herself—she might split it among the five finalists, or donate it where it’s needed, like the public library system—while Erika Vogt pointed out that there should be more discussion around the need for more funding sources within the region.7

It may well be that in our heart of hearts, having agency and building community are more important than giving one person $100,000, as Forti stressed to me. But I don’t think this means that the Mohn Award is a bad thing for Los Angeles. Veteran gallerist Thomas Solomon points out that at this critical point in its development, the local art world needs to show that there is substantial recognition and support for artists coming from within LA—without this, it is difficult to generate support from outside of the city. Meg Cranston, a mid-career biennial artist, also feels that the prize is important from a development standpoint and could help the Hammer Museum to leverage more money for other projects. As an artist who has been nominated for many prizes, Cranston offers a more philosophical take: “If anyone thinks that winning this award means that you are the best or most important artist, they are mistaken. It’s just a matter of someone’s karma lining up in a particular way to get a particular prize. It’s the luck of the draw.”

Tate director Nicholas Serota, who has played a pivotal role in the development of the Turner Prize, has admitted that he initially felt bad about the “discomfort” of artists, but eventually decided that it was a necessary evil in the quest to engage the broader public in contemporary art.8Anya Gallacio, a 2003 finalist, suggests that now that the prize has done that job, perhaps the powers that be could move on to find a more authentic way to showcase British art.9Here in Los Angeles in 2012, with the luxury of hindsight and with the pitfalls of the Turner Prize as cautionary tale, might we be able to move straight into that better phase and decide what our own agenda is going to be?

Rather than looking at the Mohn Award as either a positive or a negative, it could be looked at as an opportunity to shape what is perhaps an inevitable phenomenon to our liking. The artists themselves have already done this, and can continue to do this, by exercising their agency and talking to one another. The Hammer, which prides itself on being more of an experimental, artist-oriented laboratory for museological practices rather than a traditional museum per se, has also stated that they are open to discussing the various particulars of the biennial exhibition and the awarding of the prize going forward.10Based on feedback from their Artist Council, they have already changed the name of the award from its original moniker, the Mohn Prize, to the more serious-sounding Mohn Award. They may also convene a meeting in the fall so that the biennial artists, Jarl Mohn, and the Artist Council can discuss the future administration of the Mohn Award.

If the character of the prize’s founder is any indicator, I think the chances of a positive outcome that benefits the many rather than the few are strong. I interviewed Mohn and found him to be a regular, down-to-earth guy who very slowly developed his appreciation and his collection over the years. His passion and enthusiasm for the art and artists of the emerging LA art scene were palpable, and he is much more excited about the monographic publication than he is about the cash prize itself. “It’s going to be a limited edition and we’re going to mail them internationally to the people that we think are the real tastemakers in contemporary art—collectors, curators, critics, galleries, museums—to say, ‘look at what’s happening here.’” The book will be designed by the same team who designed the biennial catalogue and the two volumes will be bundled together as a set. “What I’d like to see, five or ten years from now,” Mohn says, “is a recognition everywhere that [Los Angeles] is the spot, and to be a real catalyst for helping careers.”

In addition to having his heart in the right place, Mohn also has a terrific sense of humor. During our interview, the Hammer’s Communications Director, Sarah Stifler, told him about the Mohn Games betting pool and he was tickled pink. “You’re shitting me! How funny! Did anybody do well? I have to go look it up. My daughters [one of whom is in graduate school for art history and curatorial studies] will go crazy. They’ll think that’s hilarious. I’d love to see if anybody nails it.”

After the interview, I was driving home when I received a phone call from Eric Kim.

“Hey Carol, do you know Jarl Mohn?”

“Yeah, I just interviewed him. Why?”

“He just matched the Mohn betting pool.”

It would appear the odds are in our favor. Like the song says, the kids are gonna be alright.